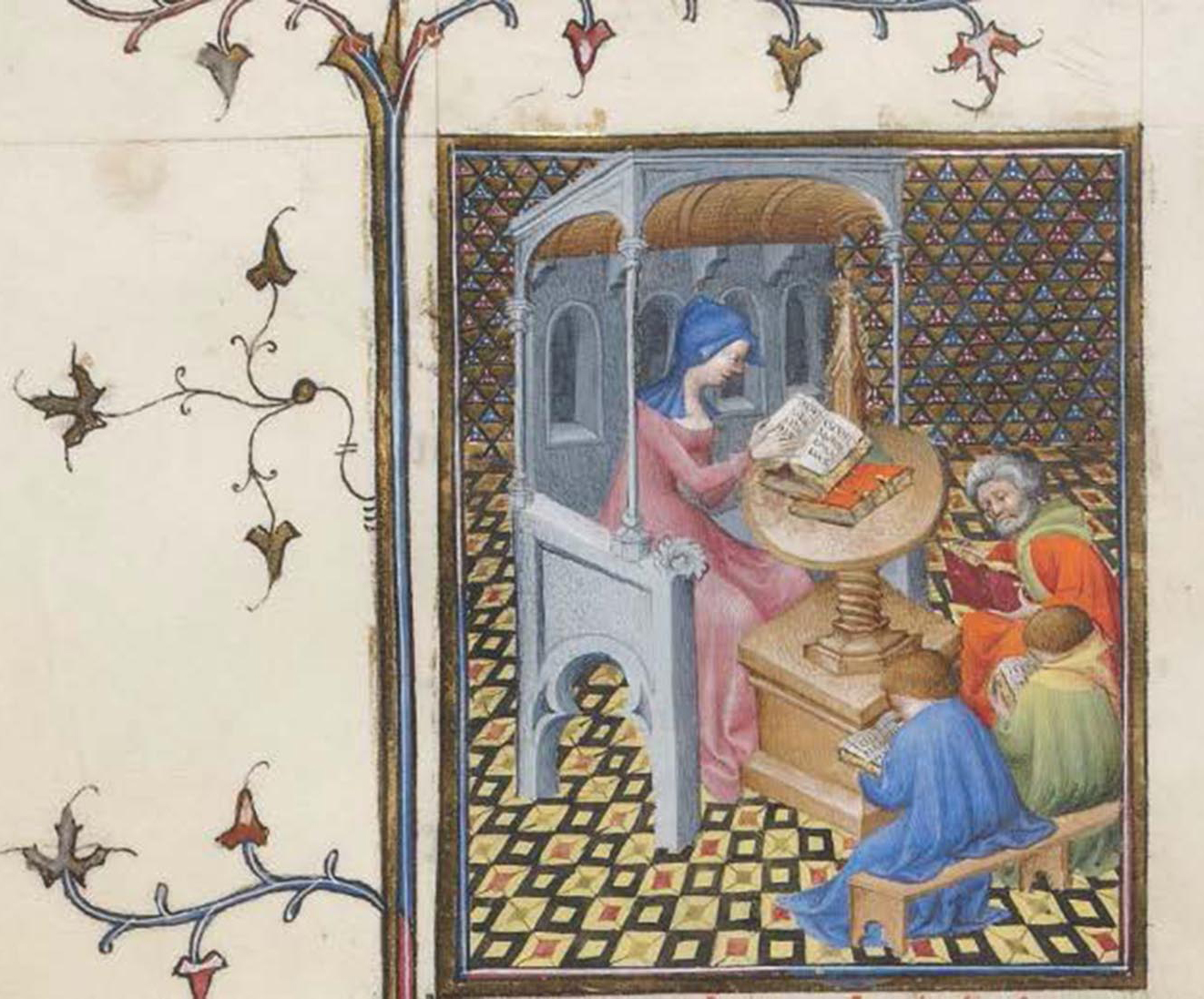

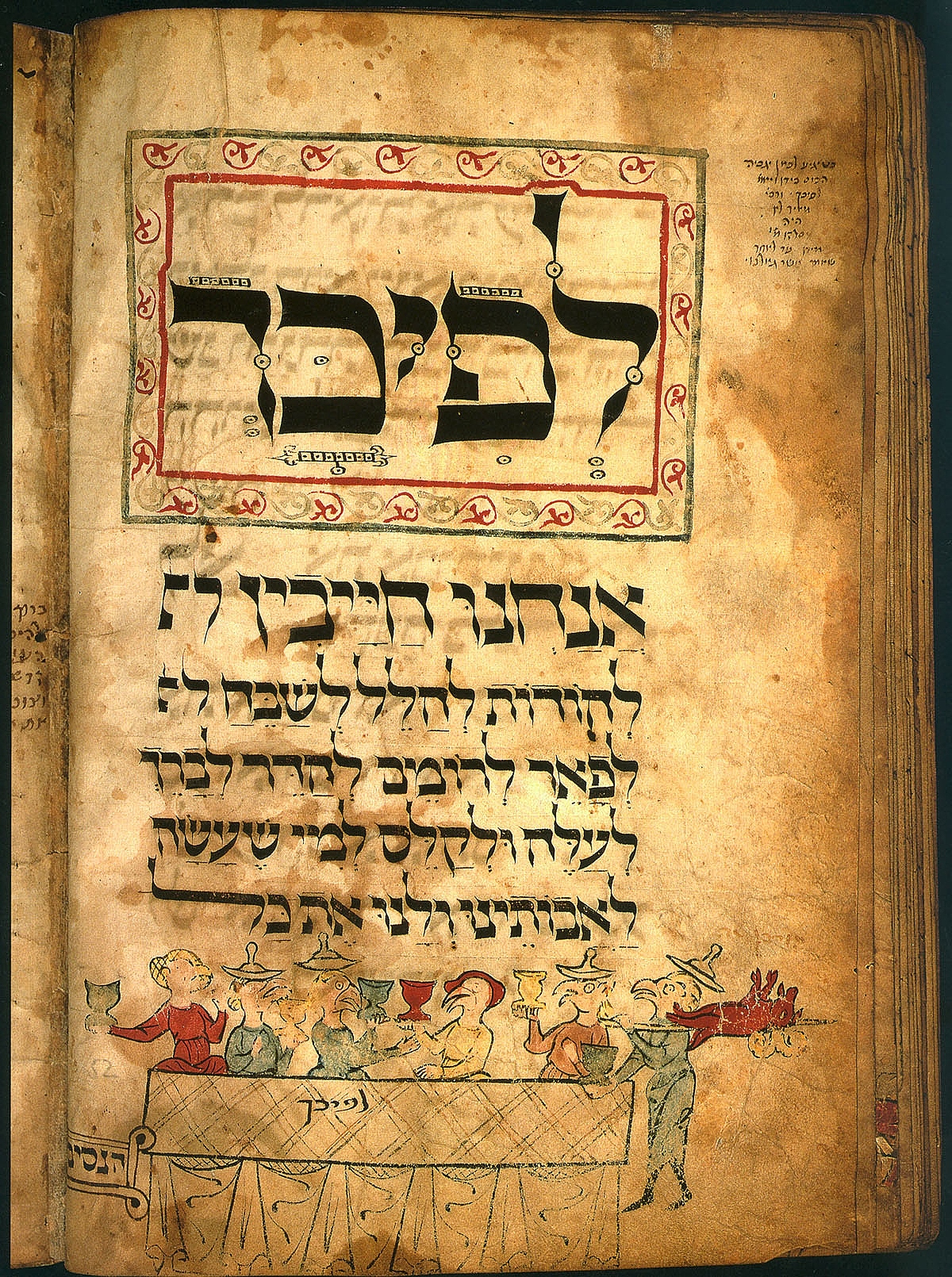

Birds’ Head Haggadah (c. 1300)

This year the Jewish celebration of Passover begins at sundown on April 22, and it ends after nightfall on April 30. Two Seder dinners will be held during Passover, and the Haggadah will be read to tell the story of the delivery of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt. The oldest extant illuminated Ashkenazi Haggadah is the Birds’ Head Haggadah (c.1300), copied and illustrated by the scribe Menahem. Not a scroll but a book, the Birds’ Head Haggadah measures 11’’x7.2’’ and contains 47 pages on parchment. Dark brown ink was used to write the text and outline the illustrations. Tempera was applied for color.

Making Matzo

The celebration of Passover is found in Exodus 12:1-28. Several scenes illustrate preparation for the Seder meal. “In the first month you are to eat bread made without yeast, from the evening of the fourteenth day until the evening of the twenty-first day.” (Exodus 12:18) The two-page illumination of making matzo starts on the right side of the page where a woman, wearing a red snood, has processed the grain. Since the original Passover occurred during the barley harvest season, matzo may have been made by mixing water with ground barley. Matzo is a flat unleavened bread. The figure in yellow is poking holes in the bread so it will not rise. The second woman with the red snood and the man in the green robe are saying a prayer over the matzo. On the next page, the man in the blue robe holds a tray of three matzo loaves, while the last figure in a red robe is baking the matzo. Since the Israelites needed to leave Egypt quickly, they had no time to allow the bread to rise.

The attire of the figures is interesting. They wear clothing appropriate to the time, but the male figures wear peaked hats. The fourth Lateran Council in 215 CE declared that male Jews must wear peaked Jewish hats. The heads of the Jews are represented by bird heads, thus the name of this Haggadah. The reason for this substitution is most likely a result of Jewish aniconism that forbids idolatry, the depiction of graven images. The bird heads have noticeably sharp beaks, which has led to speculation about the type of bird.

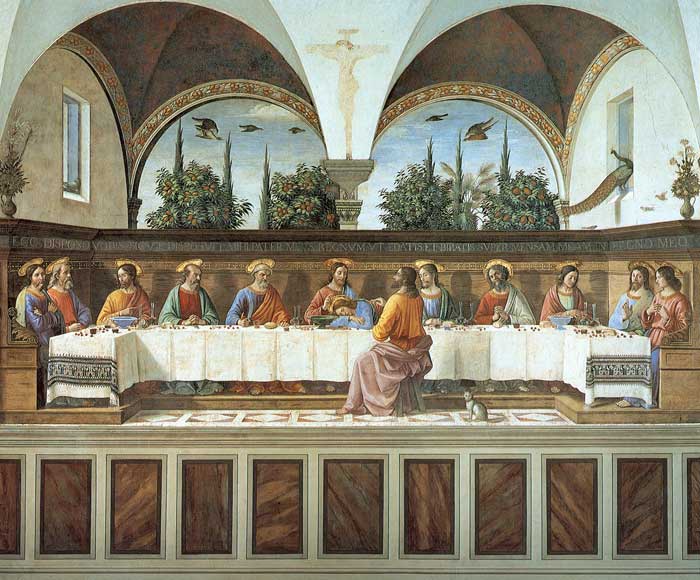

Passover Seder

At the far right of the Passover Seder, a man brings in the Paschel (Passover) lamb. “Tell the whole community of Israel that on the tenth day of this month each man is to take a lamb for his family, one for each household.” (Exodus 12:3) “The animals you choose must be year old males without defect.” (Exodus 12:5) The lamb can be identified as a male by it yellow horns. The lamb was not to be eaten with water, must have been roasted, and no bones broken. “Then they are to take some of the blood and put it on the sides and tops of the doorframes of the houses where they eat the meat.” (Exodus 12: 8) “On that same night I will pass through Egypt and strike down every first born—both man and animal.” (Exodus 12:12) The man with the lamb also holds a cup.

Five Jews are seated at the table, and each holds a cup representing one of the necessary components for the Seder plate. Unfortunately, the items are not illustrated. However, the first item on a Seder plate is the lamb shank. The second item is a roasted egg, a symbol of mourning, the first food served after a funeral. Bitter herbs or horseradish are the third item on the plate, and they represent the harshness of slavery in Egypt. Forth is haroset, a sweet brown mixture that is a symbol of the bricks and mortar used to build Egyptian structures. Fifth is a fresh green vegetable that is dipped in salt water, representing hope and renewal.

Exodus

The illumination of the Exodus covers two-pages. On the left page, Moses in the red robe and holding his staff, leads the Israelites. Behind him, four figures, with their heads raised toward heaven, carry their belongings as they leave Egypt. Two figures hold the matza. On the next page, the Pharoah, on horseback, is dressed as a European King. A knight carries a standard. The faces of the non-Jews, without bird beaks, lack features.

Two Jews, one on horseback, follow. Behind them is a carriage and some Egyptian soldiers. In the Birds’ Head Haggadah most of the men wear Jewish peaked hats, but not all do.

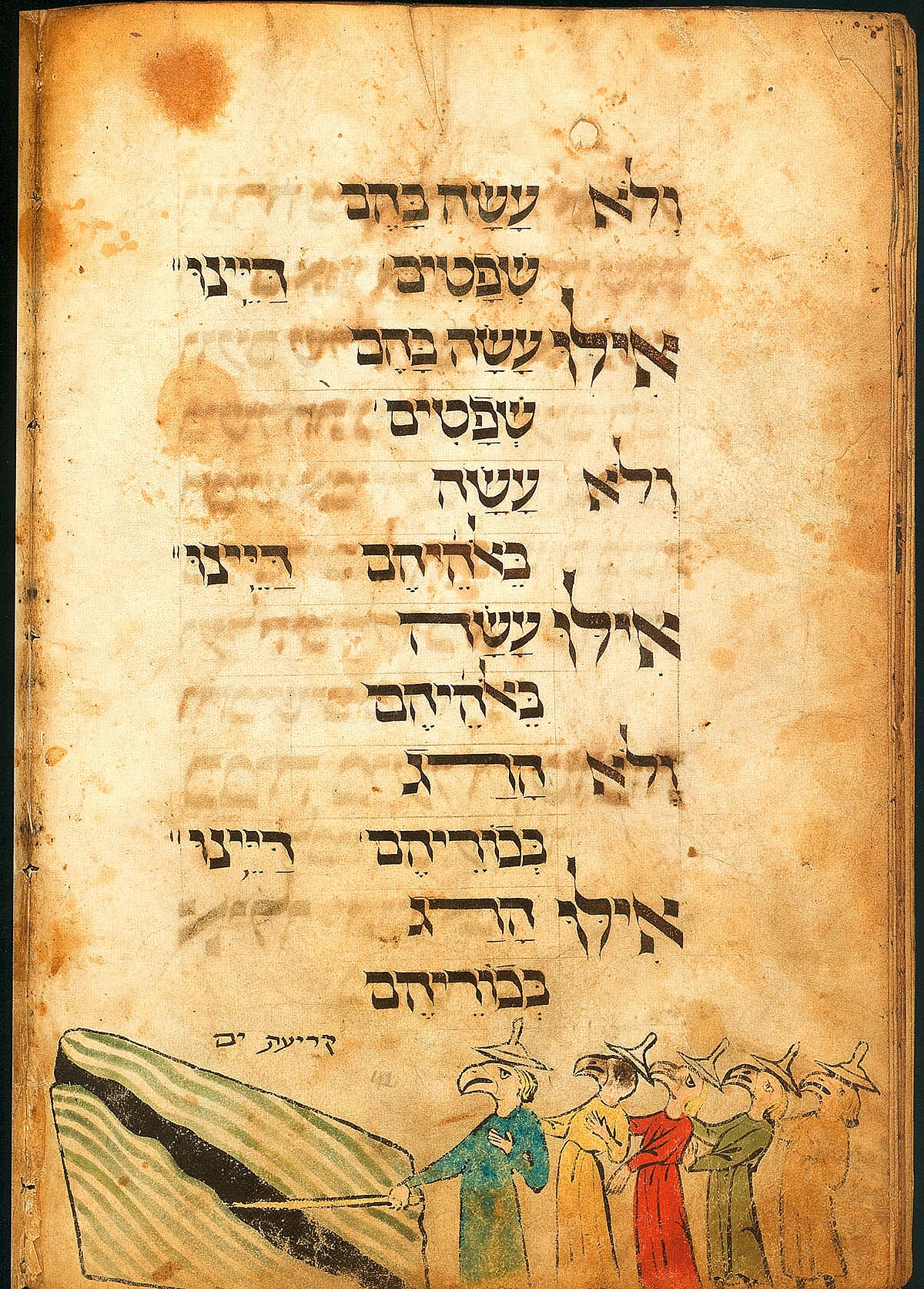

Crossing the Red Sea

Crossing the Red Sea might seem a difficult event to depict. Menachem has settled on a simple and effective solution. Moses lowers his staff and the water parts, allowing the Israelites to cross.

Manna and Quail

The Exodus story tells that the Israelites grumbled because they had no food, and God heard their cries. “I will rain down bread from heaven for you.” (Exodus 16:4) Two men lean down to gather the yellow, green, and red manna, the bread of Heaven. “That evening quail came and covered the camp” (Exodus 16:13). A red quail can be seen in the center of the illumination. The hands of God, extending from heaven, offer what appears to be matza.

On the first page of the Birds’ Head Haggadah, a man and woman sit at the Seder table. The woman passes him matzo to begin the ritual. The last page contains a depiction of the rebuilt Temple of Jerusalem.

Note: Matzo is the Ashkenazi pronunciation which deletes the letter “h” from the end of the word. Matzah can be found in both Ashkenazic and Sephardic texts.

Quotes from the Book of Exodus are taken from the New International Version of the Holy Bible.