Rachael Breen is a Minnesotan artist of Jewish descent. After receiving a BA from Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, she became a community organizer and a social justice advocate. This work took her to New York City, where she attended classes at Parsons School of Design. She had not previously pursued a career in art. When she returned to Minnesota, she enrolled in art classes at Sabes Jewish Community Center. She received an MFA from the University of Minnesota at age 42. Her commitment to social justice and art gave her the incentive “to grow my artistic voice and skills.”

“Spinach” 2011

Breen’s interest in the role of women throughout history led her to buy a $3 sewing machine for something to do before she started graduate school. Her 2011 series Historic Treasures was about biodiversity and sustainability. “Spinach” (2011), in addition to the subject vegetable, includes millet, corn, heirloom seeds, and ancient containers in which seeds were placed for transport. Fresh spinach leaves, simply drawn, surround an elaborate blue vase, perhaps emphasizing the importance of the seeds. At the left, seeds are placed on a gold scale. In 2014 she created the series Common Milkweed to raise awareness of habitat destruction of the milkweed plant, the common diet of Monarch butterflies, contributing to the significant decline of the Monarch population. She said, “That sent me on a path to research and it’s what my work has been about ever since.”

Breen was a late comer to making art, but her artistic vision coalesced in 2013 when the Rana Plaza Factory in Bangladesh collapsed, killing 1,129 garment workers, and injuring over 2,500 more. Breen recalled the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York that killed 146 young Jewish and Italian immigrant female garment workers: “Part of being Jewish is being an activist and working for social change.” With a grant from the Minnesota Jewish Arts Council, Breen and writer/poet Alison Morse traveled to Bangladesh.

The trip to Bangladesh generated several series, including Evidence (2016). Breen and Morse visited the site of the Rana Plaza factory and found burned and shredded pieces of fabric. Breen turned these items into individual works of art, sewing scraps together to create a reminder of the event. She describes the purpose of the series as “an effort to repair. The work is made in tribute to those who survive a disaster. I believe the act of remembering can be an act of resistance.” The Rana Plaza disaster led to the formation of the Alliance for Bangladesh Workers Society organized by American brands such as GAP, Walmart, and Target.

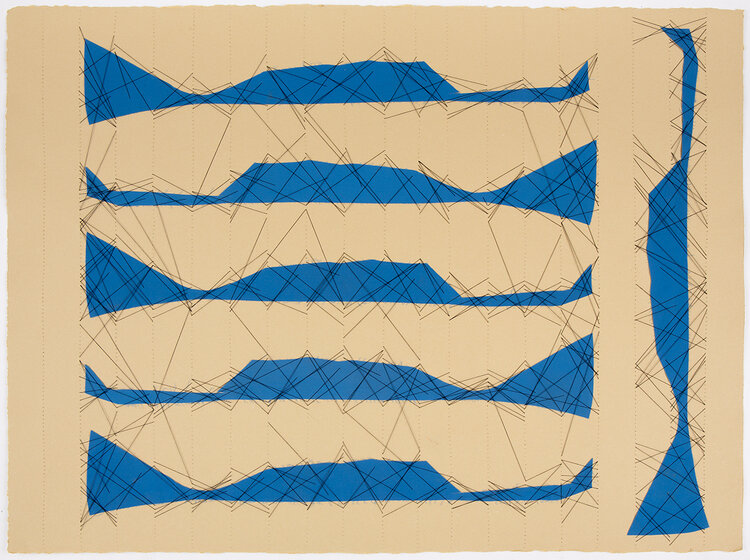

“4” (2016)

A second series, Supply Chain Maps (2016), was developed by researching factors relating to the disaster: lack of transparency, the enormous disparity between income of workers and those of wealthy shareholders, and the supply chain of the global economy. Included in the series was “4” (2016) The full title is “4, In just four days a CEO earns a garment worker’s lifetime pay.” The work is abstract and composed of fabric scraps from Bangladesh and machine sewn lines that reference the complicated system that provides clothing to the western buyer. She recalled, “When we were there, it dawned on me that women working in incredibly unsafe conditions with unfair pay would never wear the same clothes that we wear…In some ways it’s quite tedious. Part of the idea is to emphasize that this is an incredibly tedious and repetitive task that women are doing.”

Breen began in 2017 hands-on programs such as Behind the Seams in which visitors to pop-up garment factories see workers at their sewing machines, sewing re-purposed T-shirts from dawn to dusk. This interactive program enabled visitors to learn how a simple T-shirt was made, and to understand the process: raw cotton from field, to factory, to mall. Visitors could pledge to help make a change in the garment industry and to purchase one of the repurposed T-shirt for $3.

“Shroud” (2018)

“Shroud” (2018) is composed of 1,281 white shirts hanging from the ceiling. They represent the 1,281 dead workers, mostly women, from the Bangladesh and Triangle Shirtwaist disasters. The 1,129 corpses in Bangladesh were wrapped in white shrouds, also practiced in the Jewish faith. Breen hung the shirts from the ceiling with the arms hanging down. They seem to reach down to the visitors who walk beneath.

Breen added another level of meaning by purchasing the shirts from a Goodwill Outlet. Her research found that Goodwill Outlets were the last stop in the supply chain before the shirts became part of a landfill, or were placed in containers and sent to buyers in the global south. Breen priced a new white oxford shirt at Walmart at $15, and from two other stores up to $69.50. The salary women are paid to make one shirt was about 20 cents.

In

Breen explored various aspects of the garment-making process. One is piece work, the process for making various parts of shirts: sleeves, pockets, collars, button holes, and plackets. Her 2020 exhibition The Labor We Wear included several piece-work compositions, some covering an entire wall of the exhibition space. ‘’The Bottom Line” (2018) is composed of shirt plackets, where buttons are fastened. Black, white, gray, and blue plackets are arranged in a vertical composition. Breen described her process: “I played with those plackets in so many different ways and in so many different colors and arrangements…I was like, Oh my God, it makes sense. The people who wear these shirts are making decisions that impact the working conditions of the people who make them. Seeing the plackets creating a graph of the ups and downs of the stock market . . . the irony of it really hit me.”

“Collars” (2018)

Instead of making the shirts, Breen deconstructed them, a process that any women who has needed to alter a garment can understand; it is tedious and painstaking. Seeing a wall of shirt collars, viewers are reminded of tediousness, repetitive, twelve-hour days spent making shirts.

Breen was the inaugural recipient of the Jerome Hill Artists Foundation Fellowship in 2019. The Jerome Hill Fellowship was founded by New York and Minnesota artists to recognize other artists who “embrace their roles as part of a larger community of artists and citizens, and consciously work with a sense of service, whether aesthetic, social or both.” She was awarded a Fullbright Scholarship in 2022. In 2023, there were at least nine exhibitions of her work, and she was invited to give a number of lectures. Breen exhibitions number at least 50, and she continues to work. For over 25 years, she has served as a Professor of Fine Art at Anoka Ramsy Community College in Minnasota, and she teaches sewing classes on the side.

Banner for Solidarity, No. 1” (2023)

Breen’s last exhibition in 2023, At the Root: Materials and Power, ran from October to December at St John’s University in Minnasota. Having recently completed her research at the International Ladies Garments Workers Union archives, she was drawn to the huge banners produced at the start of the ILGWU in 1900. The banners were bright, colorful, and some decorated with tassels. “Banner for Solidarity, No. 1” (2023), a colorful piece-work creation is just one of Breen’s banners that pay homage to the first ILGWU members.

“While rooted in research about the garment industry, my work also refers to the scale of many crises caused by capitalism—climate change, racism, and labor abuse. It makes visible numbers and systems that are hard to comprehend, in an effort to remind us of the human labor present in the clothes we wear and our relationship to these workers. My interest in labor rights stems from histories of Jewish activism in the garment industry and also my own family history as immigrants and activist.” (Rachel Breen)

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.