Christmas with Grandma Moses

Anna Mary Robertson Moses (1860-1961) began painting at age 78. Her paintings of bygone American life were discovered in 1938, and her popularity continues to this day.

“Grandma Moses” (1953)

The Time Magazine cover on December 28, 1953, featured a portrait of Grandma Moses painted by Boris Chaliapin, along with the text “Christmas is not just one day.” Her smiling face was set in front of a snowy winter landscape with a church in the background. Moses painted all the seasons of the year and hundreds of scenes of farm life in rural America where she grew up. Among her 2000 paintings are celebrations of Christmas. She once wrote, “I forget everything, everything except how things used to be.”

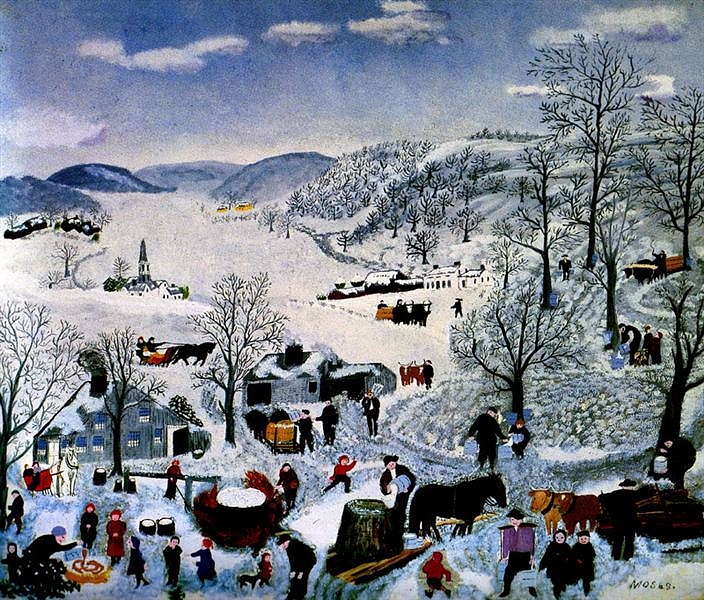

“Let Me Help”

Winter snow scenes were among Moses’s favorites, especially at Christmas. “Let Me Help” is a depiction of the community gathering to help cut Christmas trees for the nearby church, and perhaps for the farm house up the road. There are at least three trees down. In the left corner a horse and rider pull a cut tree into the scene. In the center foreground, two figures cut down a second tree. A third tree already has been cut and roped to a horse for transport. The scene includes gaily dressed villagers, some talking, a pair with a sled and a dog, and a pair with an axe. In the distance, a barn, snow-covered trees, an evergreen forest, and the cold winter sky complete the scene. As always, Moses painted a joyful and peaceful memory of days gone by.

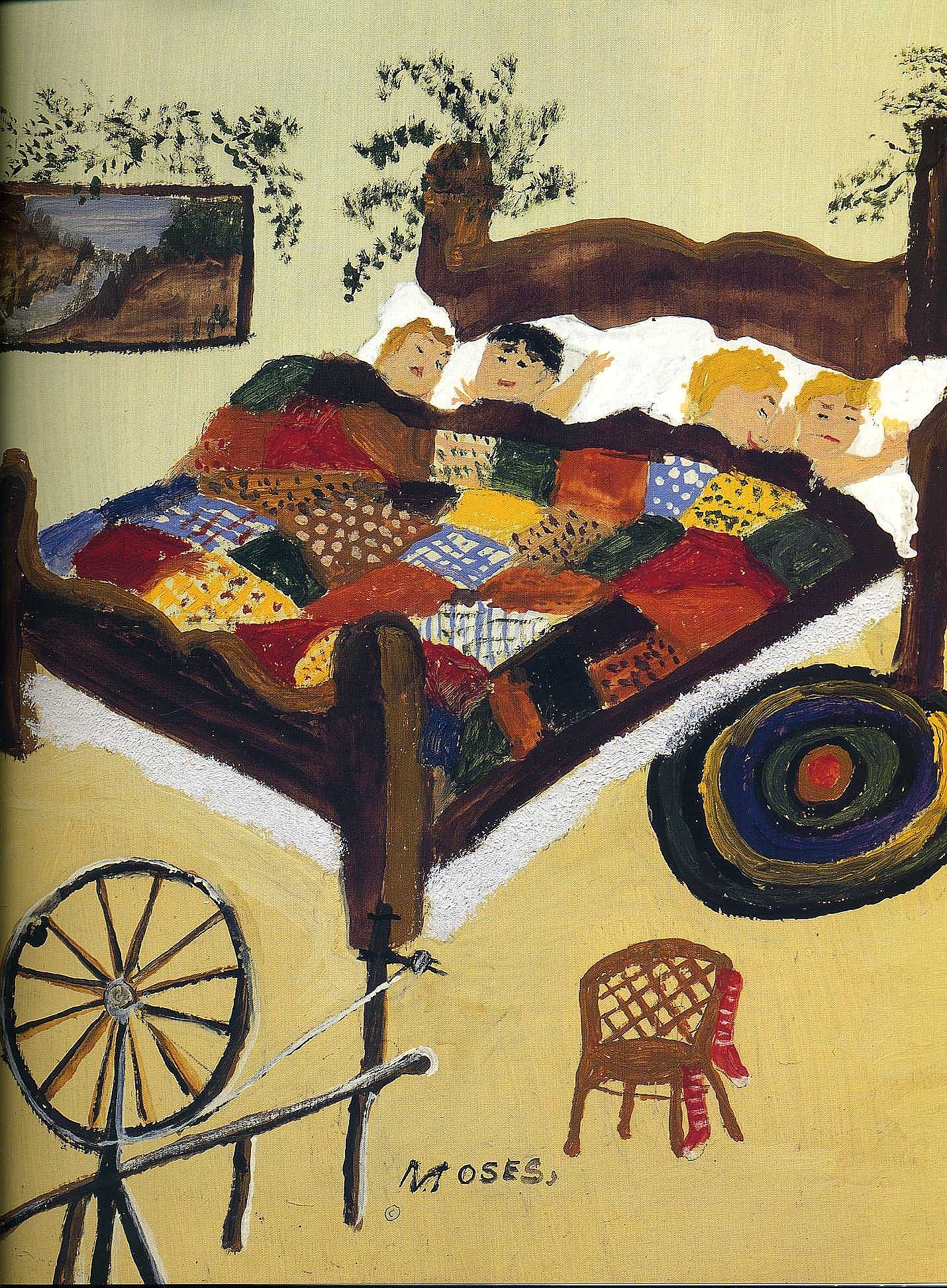

”Waiting for Christmas” (1960)

Waiting for Christmas” (1960) is an unusual painting for Moses. It is a close-up view of a bedroom in which four children are all nestled together in the heavy wood bed. They are covered with a “charm” quilt made with random shapes and no pattern. These quilts were popular in the 1870s and often contained fabric from other items used in the household. Fabrics were traded among quilt makers to obtain as many different designs as possible. Three of the children are asleep, but the child with dark hair and eyes is awake, waiting for Christmas. The head board is decorated with greens. A rumpled round woven rug is on the floor. Two red stockings are hung on the small wicker chair. A spinning wheel is set in the lower left corner of the scene.

Moses typically painted landscapes, and she used bright colors everywhere. The landscape in this painting is in a frame and hangs on the wall.

“Here Comes Santa Claus” (1948)

Moses’s Christmas images became so popular they were used on Christmas cards, other greeting cards, jam jars, curtains, and postage stamps. Hallmark sold 16 million Moses Christmas cards in 1947. “Here Comes Santa Claus” (1948) (15”x23”) is one of several paintings on this theme. The full moon lights up the snowy scene. Bright stars fill the deep blue sky. Moses painted from the sky down. Tall snow-covered trees link earth and sky. Down from the sky to the cozy house comes Santa Claus in his sleigh drawn by eight reindeer. Delightful.

KRI7286740 Down the Chimney He Goes, 1960 (oil on pressed wood) by Moses, Anna Mary Robertson (Grandma Moses) (1860-1961); 40.6×60.3 cm; Private Collection; (add.info.: Illustration for The Night Before Christmas by Clement C. Moore); Kallir Research Institute/© Grandma Moses Properties Co.

Please note: This photograph requires additional permission prior to use. If you wish to reproduce this image, please contact Bridgeman Images and we will manage the permission request on your behalf.

The same sky, stars, and trees are present. Moses features the roof top of the house on which Santa has parked his decorated yellow sleigh filled with packages. Some spill onto the roof. She manages to get all eight reindeer on the roof. Looking closer, the viewer can see a small section of Santa’s red suit sticking out the left chimney.

Grandma Moses was 100 years old on September 7, 1960. Governor Nelson Rockefeller declared her birthday, Grandma Moses Day. Life magazine published a photograph of her on its cover on September 19, 1960, with wishes for a happy 100th birthday.

“So Long till Next Year” (1960)

“So Long till Next Year” (1960) is a depiction of the end of the story as Santa waves to the viewer from his sleigh as he and his reindeer fly back to the North Pole. The landscape, including the trees, the house, and the sky, is repeated. This painting is one of the 25 Moses completed during the last year of her life. She would paint for five hours, and without an easel, in the kitchen or bedroom. She said, “I’ll get an inspiration and start painting: then I forget everything, everything except how things used to be and how to paint it so people will know how we used to live.”

Wishing everyone the very best of holidays.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.