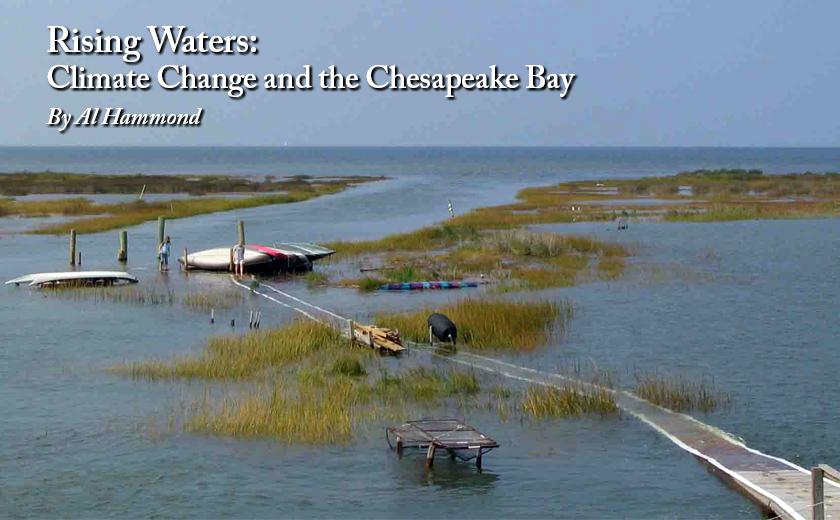

Climate change can seem a little abstract, or at least causing problems comfortably far away–forest fires in California and the Pacific Northwest, or hurricanes on the Gulf coast. But new research makes clear that there will also be profound local impacts. Recent flooding on Maryland’s eastern shore—in Salisbury, Chrisfield, Cambridge—and in Annapolis and Baltimore on the western shore is “likely just a foretaste of what is to come,” says scientist Ming Li of the University of Maryland’s Horn Point Laboratory.

The earth’s atmosphere warms because of growing concentrations of gases—especially carbon dioxide and methane stemming from human use of fossil fuels—that trap reflected sunlight. Much of that excess warmth ends up in the surface layers of the oceans. And warm water expands—raising sea levels slightly each year. This process has been accelerating in recent decades, and in Chesapeake Bay the water level is rising at twice the global rate. So high tides are getting higher, and so is the risk of flooding.

Warmer waters also mean that there is more evaporation into the atmosphere, and hence the likelihood of more (and more intense) rainfall, which can add to flooding as rivers overrun their banks. And since it is the moisture in the air that fuels the intensity of a thunderstorm or a hurricane, it’s not surprising that we are seeing more intense storms that unleash unprecedented amounts of rain—like the 60 inches that Hurricane Harvey dumped in the Houston area of Texas in 2017. Intense storms also mean high winds, like the 150 mile-per-hour winds of Hurricane Laura that battered Louisiana earlier this year, and often violent storm surges like those from superstorm Sandy that wreaked havoc in northern New Jersey and New York City in 2012. The forecast is for an increasing number of such severe storms.

Warmer waters also mean that there is more evaporation into the atmosphere, and hence the likelihood of more (and more intense) rainfall, which can add to flooding as rivers overrun their banks. And since it is the moisture in the air that fuels the intensity of a thunderstorm or a hurricane, it’s not surprising that we are seeing more intense storms that unleash unprecedented amounts of rain—like the 60 inches that Hurricane Harvey dumped in the Houston area of Texas in 2017. Intense storms also mean high winds, like the 150 mile-per-hour winds of Hurricane Laura that battered Louisiana earlier this year, and often violent storm surges like those from superstorm Sandy that wreaked havoc in northern New Jersey and New York City in 2012. The forecast is for an increasing number of such severe storms.

One instinctive response to such forecasts is to build up sea walls or levees to protect waterfront properties, but such hardened coastlines turn out to be very expensive—prohibitively so for the entire Bay. A second response is to create so-called “soft” coastlines—salt marshes or other low-lying areas that are allowed to flood and thus absorb much of the tidal or storm surge. A third response is to relocate threatened houses, roads, and other infrastructure away from the coastline—which is the policy increasingly being adopted for low-lying areas nationally by the Army Corps of Engineers and other federal and state agencies.

What actually happens when higher tides or a severe storm surge hits the Chesapeake Bay is fairly complex, however, and depends to a significant extend on what coastal management actions are taken. Ming and his colleagues have developed numerical models—based on the well-understood physics of how water flows and detailed mapping of the physical shape of the Chesapeake basin—of both tidal and storm surges in the Bay, using them to explore what happens under a wide range of conditions and coastal management strategies. One clear result is that while seawalls and other forms of hardened coastlines may protect some properties from higher tides, they also create peak tides that are dramatically higher, especially in the mid- and upper Bay. In effect, the tidal surge would propagate further up the Bay—to Baltimore and beyond. Soft coastlines, on the other hand, absorb much of the tidal energy, so that there would be a minimal increase in peak tides and much less impact in the upper Bay.

Most of the low-lying area appropriate for soft coastline management strategies lie on the eastern shore. So adopting that type of coastline management for the Bay would help prevent serious flooding in urban areas such as Annapolis and Baltimore, but at the expense of significant land-use changes and likely necessary relocation for some homes and facilities on the Eastern shore. Such a strategy would create serious equity issues, unless those impacted are fully compensated and perhaps incentivized.

The models show that storm surges pose an even greater—if more intermittent—risk than higher tides, promising both more extensive flooding and greater property loss. They are based on the impact of Hurricane Isabel, just a category 2 storm when it hit Maryland in 2003, but whose storm surge nonetheless damaged or destroyed hundreds of buildings on the eastern shore and caused severe flooding in Baltimore and Annapolis. An equivalent storm hitting the Chesapeake Bay region in 2050 when the ocean is warmer and tides higher would be expected to cause far more damage on the eastern shore and to have a storm surge in Baltimore more than 10 feet high—and that’s with soft coastlines in place; with hard coastlines, the impact in the mid and upper Bay would be greater. Property losses are estimated to be 3-4 times higher than Isabel. Ming’s model does not estimate rainfall, which could add to the flooding throughout the region.

Model-based projections about the future don’t come with guarantees, of course, but the message of this careful, detailed Horn Point Laboratory research is clear. Rising waters are inevitable; the incidence of severe storms is increasing; there will already be significant impacts in the next decade or two; and the time to prepare for them is now. Moreover, that a coordinated regional approach to coastline management—as opposed to individual actions to harden their shoreline for those that can afford it—will both reduce overall risks and share the burdens more fairly.

Al Hammond was trained as a scientist (Stanford, Harvard) but became a distinguished science journalist, reporting for Science (a leading scientific journal) and many other technical and popular magazines and on a daily radio program for CBS. He subsequently founded and served as editor-in-chief for 4 national science-related publications as well as editor-in-chief for the United Nation’s bi-annual environmental report. More recently, he has written, edited, or contributed to many national assessments of scientific research for federal science agencies. Dr. Hammond makes his home in Chestertown on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.