Edgar Allen Poe was born in Boston on January 19, 1809, and died in Baltimore on October 7, 1849. He was educated in Scotland, England, and then at the University of Virginia. Lacking funds, he left the University and moved back to Boston. He joined the army, but he was court marshalled. He then moved to Baltimore. There, he shifted from writing poetry to short stories. He published a series of them in a book titled MS. Found in a Bottle (1833). In 1835, while working as an editor of Southern Living Magazine in Richmond, Virginia, he published his first horror story “Metsengerstein.” In 1838 in Philadelphia, he published some of his best-known stories: “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” “The Pit and the Pendulum,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” and more. Poe’s work became popular internationally, largely through the French poets Charles Baudelaire and Stephane Mallarme.

“The Pit and the Pendulum” was published in 1842 in The Gift: A Christmas and New Year’s Present in 1843. Published annually for Christmas, it was a collection of short stories, poems, and essays with Christmas themes varying from families to the supernatural. Popular during the Victorian era, it is a beloved tradition today.

“I saw them fashion the syllables of my name.” (1919)

“I saw them fashion the syllables of my name.” (1919) is an illustration from “The Pit and the Pendulum” in Tales of Mystery and Imagination. It was published in London by George G. Harrap and Co. and illustrated by Irish artist Henry Patrick Clarke (1889-1931), known best as a book illustrator and stained-glass artist. He created 24 images for the story. The publisher commented that “there could be little doubt but that Poe’s bizarre and gruesome fancies would offer ideal inspiration to an artist of Clarke’s particular bent.” The story takes place during the Spanish Inquisition and is told by an anonymous narrator. The crime is never disclosed, but the sentence and torture are described by Poe in excruciating detail: ”I was sick—sick unto death with that long agony; and when they at length unbound me, and I was permitted to sit, I felt that my senses were leaving me. The sentence—the dread sentence of death—was the last of distinct accentuation which reached my ear.”

“I saw the lips of the black-robed judges. They appeared to me white—whiter than the sheet upon which I trace these words—and thin even to grotesqueness; thin with the intensity of their expression of firmness—of immovable resolution—of stern contempt of human torture…I saw them writhe with a deadly locution. I saw them fashion the syllables of my name; and I shuddered because no sound succeeded.”

“And then my vision fell upon the seven tall candles upon the table. At first they wore the aspect of charity, and seemed white slender angels who would save me; but then, all at once, there came a most deadly nausea over my spirit, and I felt every fiber in my frame thrill as if I had touched the wire of a galvanic battery, while the angel forms became meaningless specters, with heads of flame, and I saw that from them there would be no help.”

“They swarmed upon me in ever accumulating heaps.” (1919)

The monologue goes on to describe his confinement in a circular room. He is fed and he sleeps. When he awakens, he finds himself strapped to a board, and then notices something else: “In one of its panels a very singular figure riveted my whole attention. It was the painted figure of Time as he is commonly represented, save that, in lieu of a scythe, he held what, at a casual glance, I supposed to be the pictured image of a huge pendulum such as we see on antique clocks. There was something, however, in the appearance of this machine which caused me to regard it more attentively. While I gazed directly upward at it (for its position was immediately over my own) I fancied that I saw it in motion. In an instant afterward the fancy was confirmed. Its sweep was brief, and of course slow. I watched it for some minutes, somewhat in fear, but more in wonder. Wearied at length with observing its dull movement, I turned my eyes upon the other objects in the cell.” Rats were everywhere. “They swarmed upon me in ever accumulating heaps.”

Henry Patrick Clarke embraced the then popular Art Nouveau style of strong sinuous curves, asymmetrical design, stylized flowers and vines, and rejection of rigid geometry. He illustrated stories by Hans Christian Anderson and poems by John Keats, among others. Commissions were plentiful for his work in stained-glass.

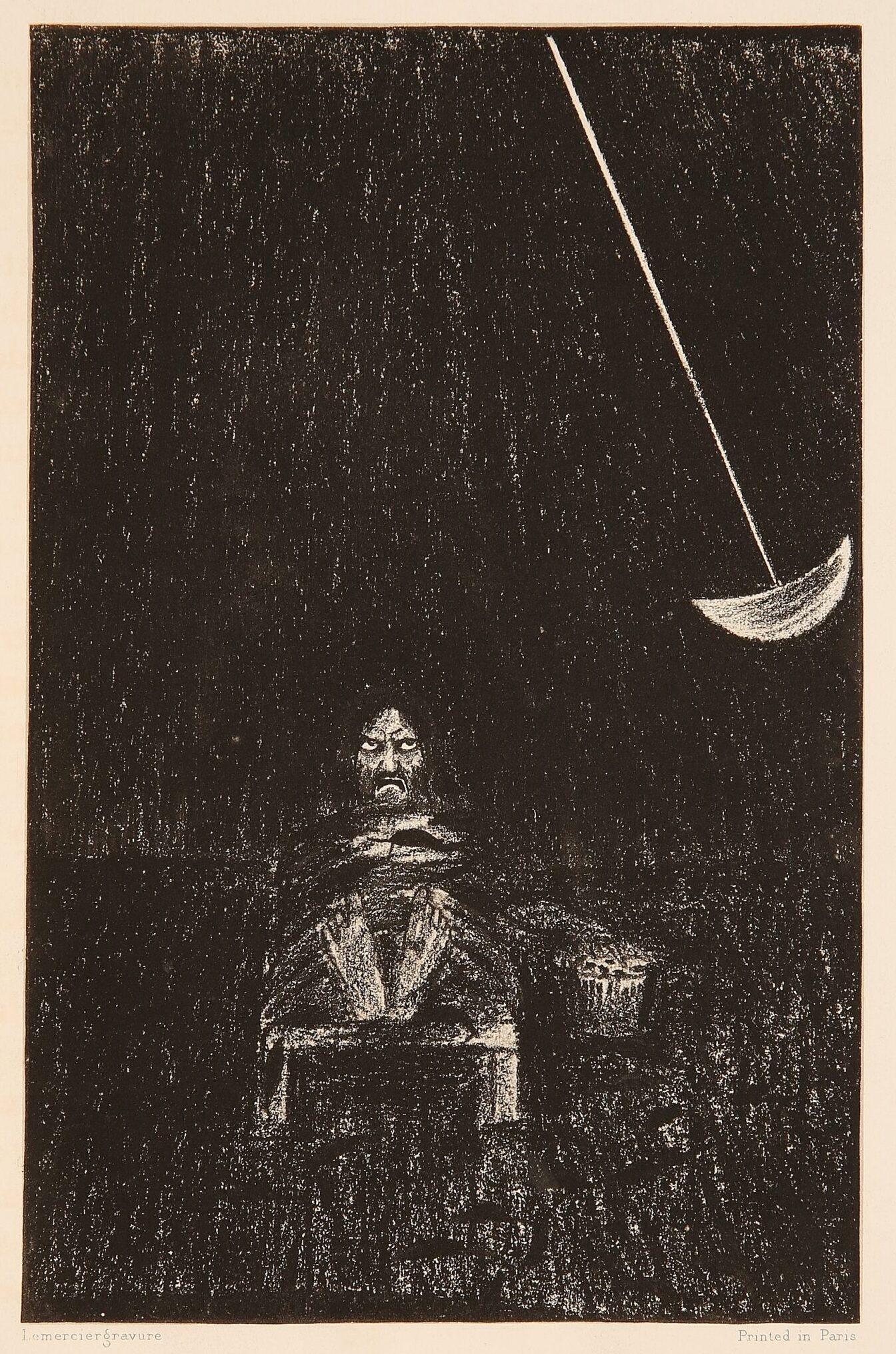

“I saw that some ten or twelve vibrations would bring the steel in actual contact with my robe.” (1899)

William Thomas Horton (1864-1919) was a Belgian-English writer and artist who studied at the Royal Academy in London. He illustrated the combined book of Poe’s “The Raven” and “The Pit and the Pendulum” that was published by Leonard Smithers in 1899. Horton was an occultist who studied the supernatural world through magic, alchemy, astronomy, and the reading of tarot cards. His drawings were left mostly unpublished during his lifetime. Horton’s illustration of Poe’s story emphasizes the darkness of the cell, the watchful and frightened look on the prisoner’s face, the menacing pendulum, and the small basket of food.

The narrator continues: “The sweep of the pendulum had increased in extent by nearly a yard. As a natural consequence, its velocity was also much greater. But what mainly disturbed me was the idea that it had perceptibly descended. I now observed—with what horror it is needless to say– the under edge evidently as keen as that of a razor…it seemed massy and heavy…it was appended to a weighty rod of brass, and the whole hissed as it swung through the air.”

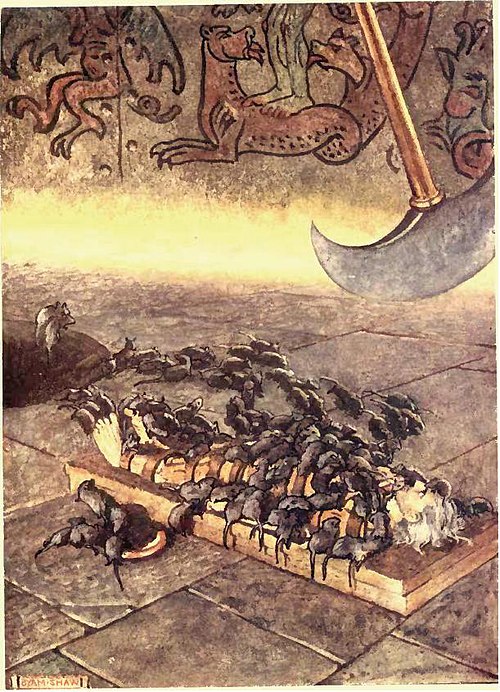

“They swarmed upon me in ever-accumulating heaps” (1909)

Poe’s Selected Tales of Mystery was published by Sidgwick & Jackson in London, and it was illustrated by John Byum Shaw (1872-1919). Shaw was a British painter, illustrator, designer, and teacher. He was encouraged by the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais to study art at King’s College London. Shaw illustrates in some detail Poe’s description of the rats, the stone floor, and on the upper wall of the cell he painted demons of hell torturing the damned. Later the prisoner will see “for the first time, the origin of the sulphureous light which illumined the cell. It proceeded from a fissure, about half an inch in width, extending entirely around the prison at the base of the walls, which thus appeared, and were, completely separated from the floor. I endeavored, but of course in vain, to look through the aperture.”

The narrator continues: “Inch by inch—line by line—with a descent only appreciable at intervals that seemed ages—down and still down it came! Days passed—it might have been that many days passed—ere it swept so closely over me as to fan me with its acrid breath…I wearied heaven with my prayer for its more speedy descent. I grew frantically mad, and struggled to force myself upward against the sweep of the fearful scimitar. And then I felt suddenly calm, and lay smiling at the glittering death, as a child at some rare bauble.”

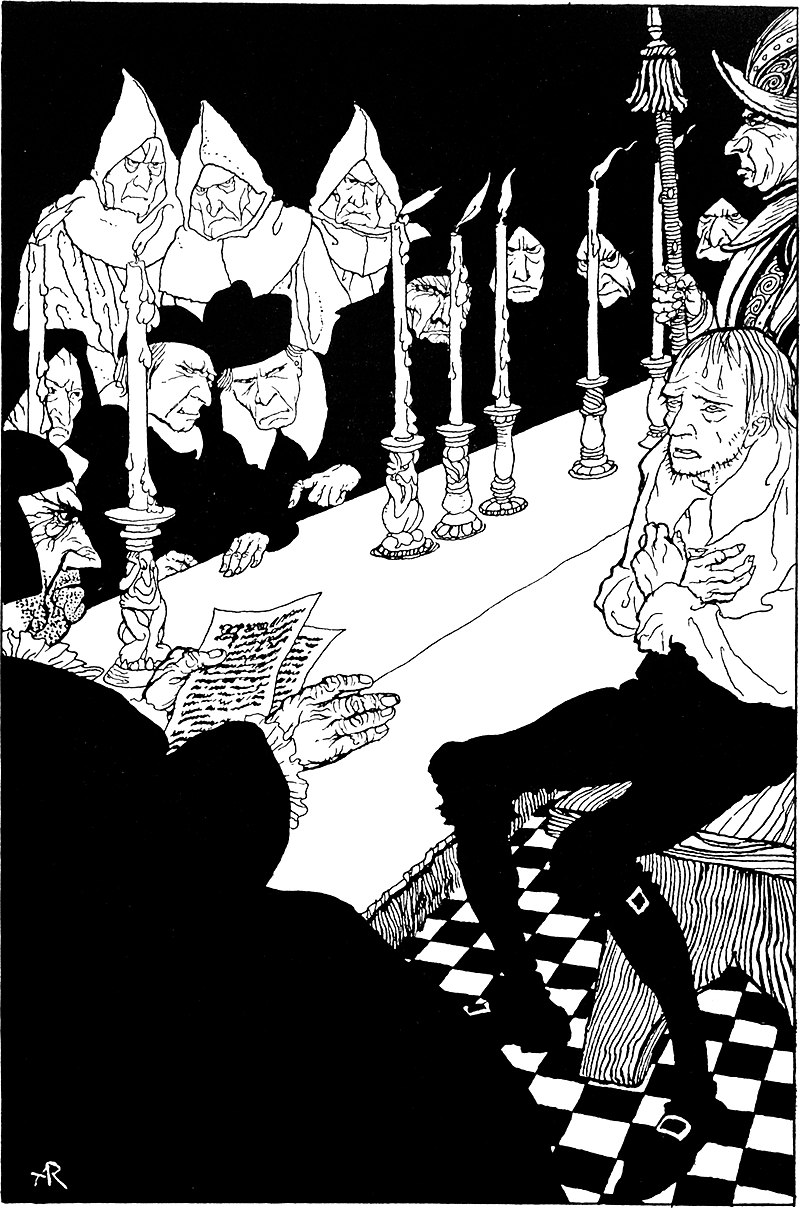

“The sentence—the dread sentence of death—was the last of distinct accentuation which reached my ear.” (1935)

Many artists have illustrated Poe’s stories and poems. One of the most famous and prolific was British illustrator Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). Among the many books are Gulliver’s Travels, Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, Peter Pan, Wagner’s The Ring, and Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination (1935) that included 12 color and 17 black and white plates. In this illustration the judges of the Inquisition pronounce the sentence. The narrator: “The sentence—the dread sentence of death—was the last of distinct accentuation which reached my ear.”

“Down–still unceasingly down—still inevitably down! I gasped and struggled at each vibration. I shrunk convulsively at its every sweep.” (1935)

The plight of the prisoner tied down is the subject that every illustrator of the story chooses. Rackham’s version illustrates the pit and the hordes of rats coming out of it to eat the food. The narrator continues the story: “With the particles of the oily and spicy viand which now remained, I thoroughly rubbed the bandage wherever I could reach it; then, raising my hand from the floor, I lay breathlessly still.”

“At first the ravenous animals were startled and terrified at the change—at the cessation of movement. They shrank alarmedly back; many sought the well. But this was only for a moment. I had not counted in vain upon their voracity. Observing that I remained without motion, one or two of the boldest leaped upon the frame-work, and smelt at the surcingle. This seemed the signal for a general rush. Forth from the well they hurried in fresh troops. They clung to the wood—they overran it, and leaped in hundreds upon my person. The measured movement of the pendulum disturbed them not at all. Avoiding its strokes they busied themselves with the anointed bandage. They pressed—they swarmed upon me in ever accumulating heaps. They writhed upon my throat; their cold lips sought my own; I was half stifled by their thronging pressure; disgust, for which the world has no name, swelled my bosom, and chilled, with a heavy clamminess, my heart. Yet one minute, and I felt that the struggle would be over. Plainly I perceived the loosening of the bandage. I knew that in more than one place it must be already severed. With a more than human resolution I lay still.”

‘’But the moment of escape had arrived. At a wave of my hand my deliverers hurried tumultuously away. With a steady movement—cautious, sidelong, shrinking, and slow—I slid from the embrace of the bandage and beyond the reach of the scimitar. For the moment, at least, I was free.”

Well, maybe.

“At length for my seared and writhing body there was no longer an inch of foothold on the firm floor of the prison.” (1935)

Poe and Rackham take both reader and viewer to what seems to be the very end. The narrator continues: “At length for my seared and writhing body there was no longer an inch of foothold on the firm floor of the prison…Even while I breathed there came to my nostrils the breath of the vapor of heated iron! A suffocating odor pervaded the prison!…A richer tint of crimson diffused itself over the pictured horrors of blood…“Death,” I said, “any death but that of the pit!” Fool! Could I resist its glow? or, if even that, could I withstand its pressure?…I shrank back—but the closing walls pressed me resistlessly onward. At length for my seared and writhing body there was no longer an inch of foothold on the firm floor of the prison. I struggled no more, but the agony of my soul found vent in one loud, long, and final scream of despair. I felt that I tottered upon the brink—I averted my eyes—”

“There was a discordant hum of human voices! There was a loud blast as of many trumpets! There was a harsh grating as of a thousand thunders! The fiery walls rushed back! An outstretched arm caught my own as I fell, fainting, into the abyss. It was that of General Lasalle. The French army had entered Toledo. The Inquisition was in the hands of its enemies.”

HAPPY HALLOWEEN

Note: Quotations of Poe’s writing were taken from several on-line sources.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.