The Library Guy, Bill Peak, speaks with Ann Finkbeiner, author of an article in the November edition of Scientific American entitled, “Orbital Aggression: How do we prevent war in space?” Finkbeiner explains why America depends so heavily on its satellite fleet, how our global adversaries are already toying with the idea of destroying those satellites, and how a major attack upon them could, quite literally, endanger civilization.

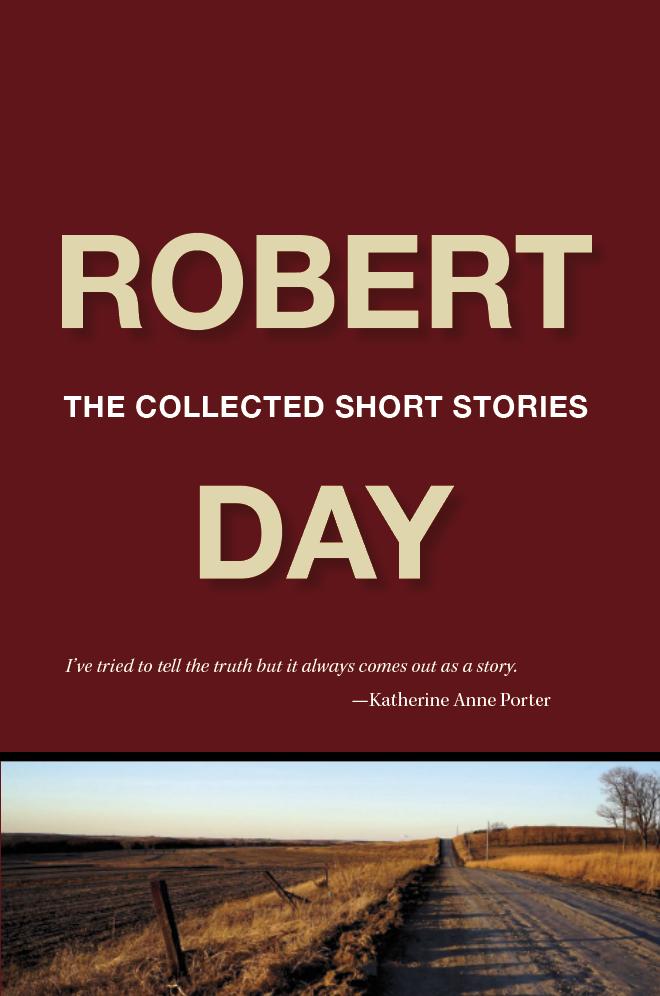

Robert Day’s second persona is his cowboy one. Once referred to as the “Cowboy of the Chesapeake,” Mr. Day hails from deep in the backcountry of western Kansas. Once upon a time, he played some serious baseball at the University of Kansas before turning to writing and penning his first successful novel, The Last Cattle Drive which was optioned for Hollywood movie rights, but alas, that tale ends with the word “optioned.” Undismayed, a few years later, Day drew upon those same Kansas roots to deliver a fine collection of stories, Speaking French in Kansas. Fortunately for his fans, that same laconic twang can be still heard in his latest work, For Not Finding You.

Robert Day’s second persona is his cowboy one. Once referred to as the “Cowboy of the Chesapeake,” Mr. Day hails from deep in the backcountry of western Kansas. Once upon a time, he played some serious baseball at the University of Kansas before turning to writing and penning his first successful novel, The Last Cattle Drive which was optioned for Hollywood movie rights, but alas, that tale ends with the word “optioned.” Undismayed, a few years later, Day drew upon those same Kansas roots to deliver a fine collection of stories, Speaking French in Kansas. Fortunately for his fans, that same laconic twang can be still heard in his latest work, For Not Finding You.