Epiphany was celebrated on Tuesday, January 6, this year. The King James Version of the Book of Matthew tells the story: “There came wise men from the east to Jerusalem, Saying, “Where is he that is born King of the Jews, for we saw his star in the east, and are come to worship him?” (2:1-2) Then “the star, which they saw in the east, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was.” (2: 9)

The Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden (c.1400-1464) was commissioned to paint more than one version of the Nativity story and the Adoration of the Magi.

”Nativity” (1445-50)

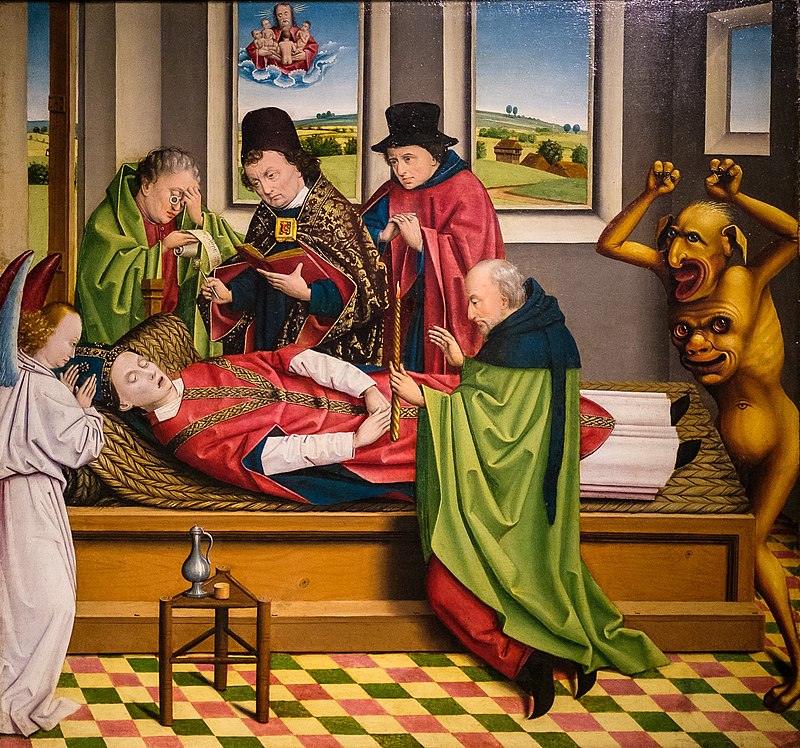

This van der Weyden “Nativity’’ (1445-50) (8’x4’) is a triptych with two folding wings. The center Nativity scene takes place in a stable with a thatched roof. The brick walls and classical columns reference European and Roman structures. The three windows are symbols of the Trinity. The elderly Joseph kneels and holds a single lighted candle. Angels attend the birth. A white dove, a symbol of the Holy Spirit, perches on the roof beam. An ox and ass are part of the scene. At the left and in the distance, an angel appears to the shepherds.

The altarpiece is known as the Middleburg Altar and the Bladelin Altar. The new church in Middleburg was built by the commissioner of the altar, Pieter Bladelin (1410-1472), who served as treasurer for Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. Bladelin is the figure dressed in the fur-trimmed black tunic and kneeling in prayer.

The painting on the panel on the left side is a scene in which the Roman Emperor Augustus, while consulting the Tiberian Sibyl as to who was the most powerful man, saw a vision of Mary and Christ. The stain glass panels in the window include the Hapsburg double-headed eagles. Augustus, like King Philip the Good of Flanders, recognized Christ as King.

The panel on the right side contains the scene of the Magi, kneeling and looking up at the Star. Van der Weyden added the figure of the Christ child in the center of the star. The Magi are dressed in rich brocades, fur, and satins typical of Flemish dress of the time. They represent the three ages of man.

Magi, the old Persian name for the priests of Zoroaster, meant they were not kings, but wise men with knowledge of astronomy, medicine, and divination. They were gentiles. They brought three gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh, and therefore were numbered as three. The names Melchior, Caspar, and Balthasar first appeared in the 6th Century CE. By the 12th Century they represented the three ages of man. In the 15th Century, wider trade led to their being thought of as travelers from Europe, Asia, and Africa. Eventually Melchior was depicted as old, Balthasar as African and middle aged, and Caspar as European and the youngest.

“The Three Kings Altar’’ (1450-56)

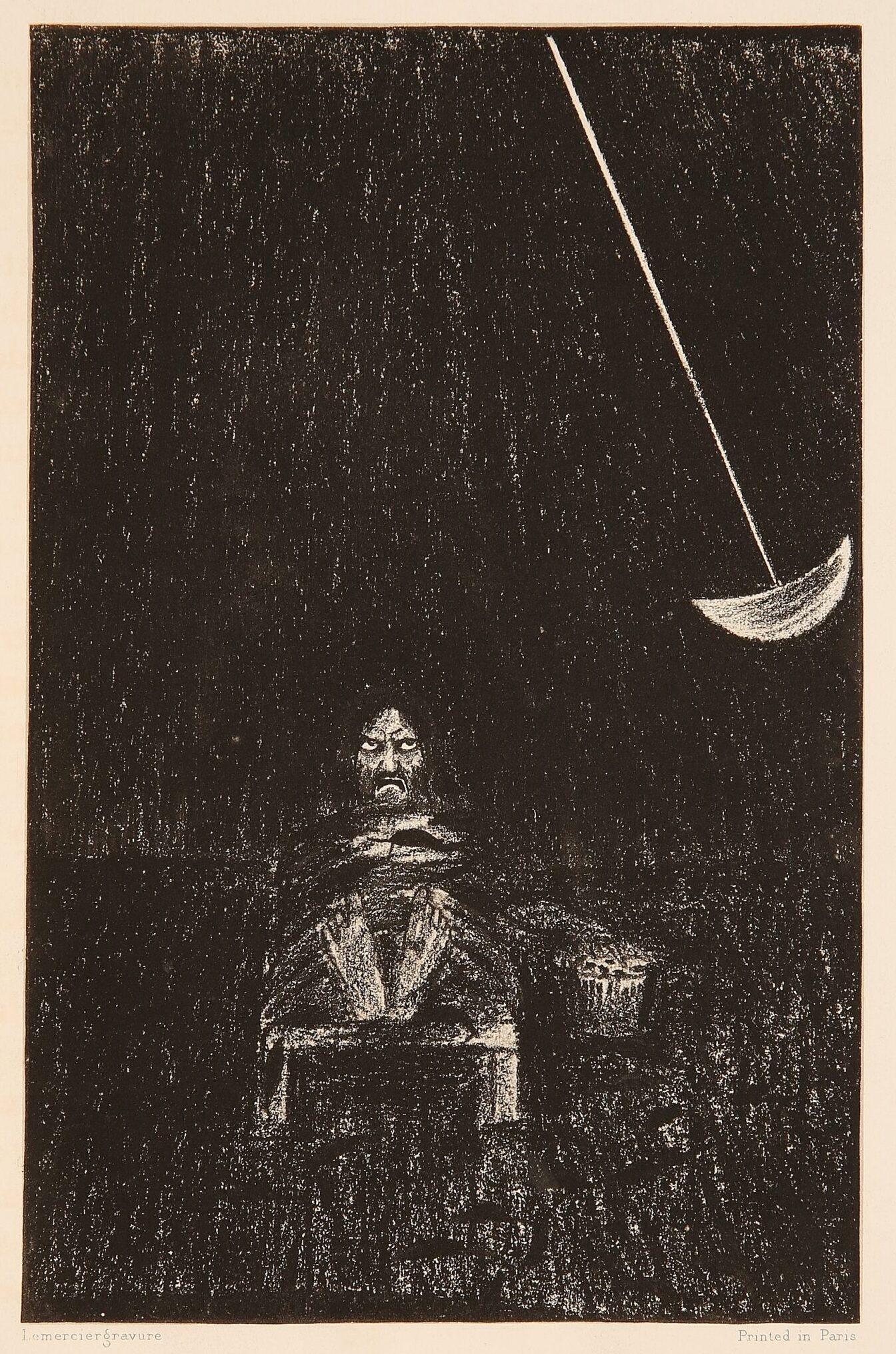

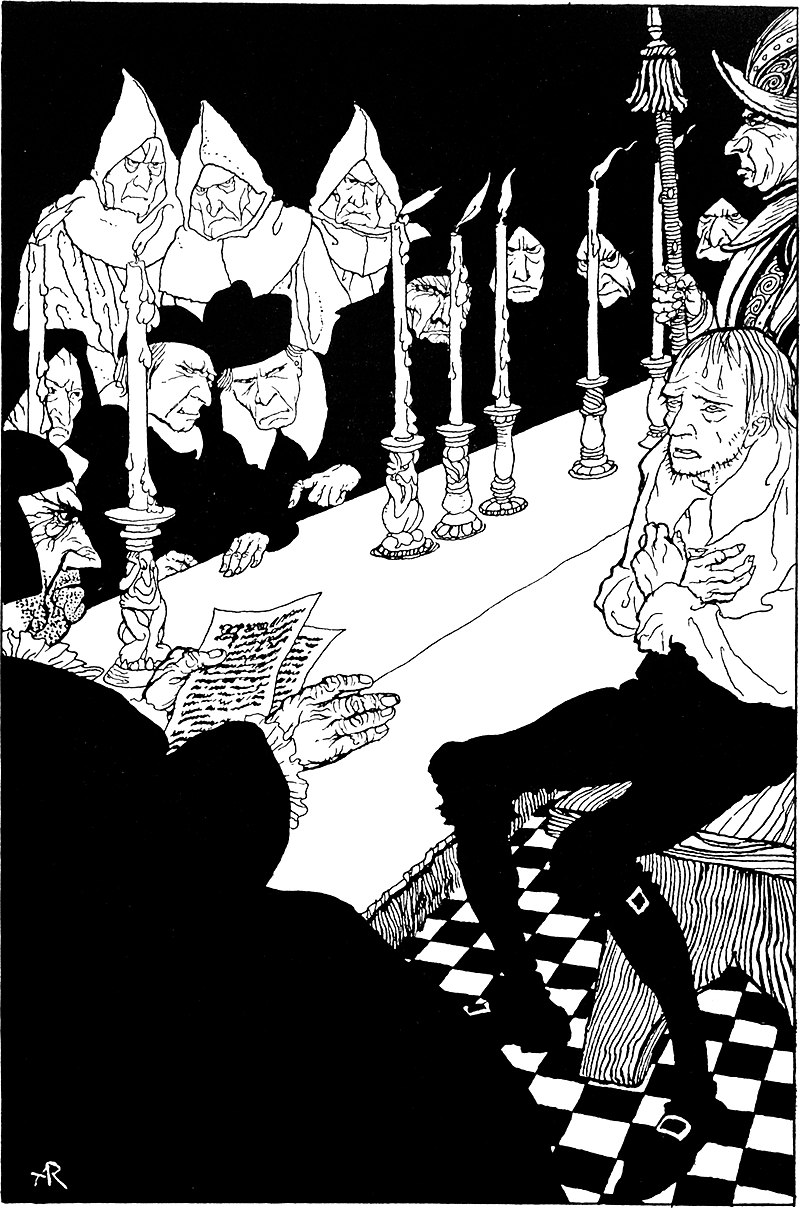

“The Three Kings Altar’’ (1450-56) (54’’x60’’) was painted near the end of van der Weyden’s life for the Church of St Columba in Cologne. The stable has no walls and is in disrepair. The thatched roof is in shambles. One interesting addition is the small crucifix hung on the central stone column. It forecasts what was to come. The Gospel of Matthew describes the event: “And when they were come into the house, they saw the young child with Mary his mother, and fell down, and worshipped him: and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense and myrrh.” Melchior, having removed his hat, kneels at Mary’s side, holding the Christ child’s feet and kissing his hand as if he were a King. Balthasar, not represented as an African, holds a gold container of frankincense and begins to kneel. Caspar removes his hat and waits his turn. All are lavishly dressed. Joseph, holding his cane, looks on from the left. The three-legged stool, symbol of the Trinity, perhaps holds the gift of gold from Melchior. Behind Joseph, the donor kneels outside the stable, rosary in hand. The ox and the ass look on. The panoramic scene set behind the stable presumably represents Cologne. A number of citizens already have reached the stable. Many others walk down a distant path to the stable.

The left panel contains a scene of the beginning of the Christmas story, the annunciation to Mary. The right panel contains a scene of Mary and Joseph taking Christ to the temple to be blessed. As was the custom, they bring with them a basket containing two doves that will be offered to buy back their son.

The Venerable Bede (673-735) described the gifts Christ was given as both practical and symbolic. Gold represented His royalty; frankincense, used in religious services, His divinity; and myrrh, used in burials, His mortality. In the 12th Century, St Bernard suggested a more practical reason for each gift. Gold would be useful for their life in Egypt, frankincense would help with the smells of the stable, myrrh that would drive out worms.

Shrine of the Three Kings (1180-1225)

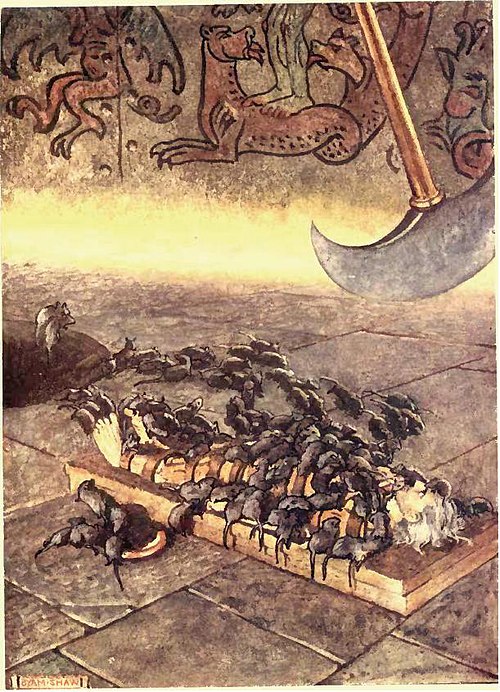

Shrine of the Three Kings (1180-1225) (43” wide x 60” high x 87” long) is a reliquary that holds the bones of the Three Wise Men created by Nicholas of Verdun (c.1130-1205), a Mosan goldsmith, metalworker, and enamellist. The shrine is placed behind the high altar of the Cathedral of Cologne. Nicholas was from Verdun, France, on the Meuse River. Mosan refers to the architecture, sculpture, stone carving, metal work, and manuscript style of the first golden age of Netherlands art.

The bones of the Magi were found by Empress Helena, mother of Constantine I, and she brought them to Constantinople. In 314 she gave them to Bishop Eustorgius of Milan. Helena was known to have found many relics. The city of Milan was conquered by Cologne, and the bones were taken there as spoils of war. Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV gave the three crowns of the Magi to Cologne and donated material to complete the shrine.

Shrine of the Three Kings (close view)

Nicholas constructed the shrine in the shape of a basilica covered with gold and silver. It is decorated with seventy-four high-relief figures that represent the prophets, apostles, evangelists, and the Three Kings. Scenes include the Adoration of the Magi, Mary Enthroned with Christ, Baptism of Christ, and the Last Judgment. Filigree designs, enamels, and more than 1000 jewels and beads decorate the exterior. The shrine holds the skulls of the Magi, wearing their crowns, and their bones. The Shrine was considered so magnificent and important that the cathedral was rebuilt in 1248 to be worthy of it.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.