Larry White and his team are prepared to start Phase One of their flood mitigation project in Cambridge. On January 17, Mayor Steve Rideout and City Manager Tom Carroll received notice from Senator Chris Van Hollen that the city was being awarded a design grant for $1.7 million, plus $85,000 for grant management. Phase One will extend to August 5 of next year.

FEMA is reserving $16 million for Phase Two, the construction. The full Shoreline Flood Risk Reduction Project, which is expected to take three to four years, is part of the ambitious Make Cambridge Resilient Initiative. That came out of the Maryland Commission on Climate Change’s flood-mapping estimate that the city will experience a sea level rise of two feet by 2050 and three feet by 2100 due to elevating storm activity.

The initiative will develop a citywide green (nature-based) infrastructure plan, make Cambridge resilient in all city planning, support businesses and residents in reducing flood risk and stormwater runoff, and develop and implement a plan to maintain the city’s flood and stormwater management infrastructure.

While awaiting FEMA’s release of the design funding, White and co have developed a work plan. They have support agreements with BayLand Consultants and Designers Inc. of Hanover, who will do the initial design. Then they will go out and collect data.

“We’ll do some borings,” said White, “we’ll do samples offshore so we can map the existing conditions, and then we’ll share that with the university.”

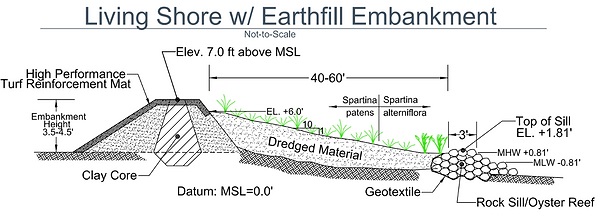

The University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science at Horn Point Laboratory will do more sophisticated modeling that includes dimensions—the slope and length of a living shore as well as the height of a rock sail—so they can predict the behavior of the shoreline. UMCES will also assess the effectiveness of the flood mitigation project against projected sea level rise and major storms in the latter part of the 21st century to show that they will be absorbing energy instead of reflecting it.

“Once we’ve finished our detailed design and refined our benefit cost analysis and done our environmental impact reporting, then FEMA will review that and approve it,” said White. “And we don’t know how long that’s going to take. Let’s say it’s three or four months. Then they would release funding for construction.”

At that point, White and co. would bring on a general contractor. They’re beginning to research qualifications now, because it’s a complex project. Also, they are identifying sources of material themselves rather than relying on the contractor for that.

There is the expectation of two grants from the Maryland Department of Natural Resources Waterway Improvements grant program for dredging Jenkins Creek and Lodgecliffe Canal for material to use for the living shoreline. Mayor Rideout recently sent a letter to the US Army Corps of Engineers navigation branch requesting the dredging of Cambridge Harbor and Channel for additional material.

That material would be used not only for the living shoreline but also for economic development. It would go toward Cambridge Harbor, the Richardson Maritime Museum, and the Yacht Maintenance Company. Dredging is approved down to 25 feet in the harbor, and there are currently places where it’s only 19 or even nine feet.

“So, it is time to do it,” said White. “It was 50 years ago when they dredged it the last time, and they used the dredge material to create Gerry Boyle Park at Great Marsh.”

Speaking of Gerry Boyle Park, White’s team is looking at making it part of the stormwater storage system. That would mitigate the need for hard infrastructure; the park could be deliberately flooded and allow the water to percolate through the soil.

“So, you end up with not only stormwater management, but you improve water quality,” said White.

But the shoreline, while primary, is still only part of the project. Two community development grants the city applied for, and which are currently in the governor’s budget, would cover the purchase and development of the acre parcel behind the old Mill Street school. That land would become the Mill Street Nature Way Park. Once the funding is awarded, White’s team will invite residents to participate in a detailed design of the project.

Another grant application was submitted to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, in collaboration with UMCES, for five and a half million dollars toward the design and construction of habitat restoration features in the living shoreline. This funding would enable the project team to enhance the ecological benefits of the project, including a small oyster reef at the toe of the living shoreline that will grow to deal with the rising water.

White’s team will begin new public outreach sessions in mid-March. Besides providing updated information on the project, they will bring in speakers to educate the citizens on what they can do to reduce personal risk, whether it’s in home or business. Also, the team will speak with the residents directly affected by the project in the neighborhoods.

“You really need community involvement,” said White. “You need to educate the public on what the problem is because they have to be part of the solution.”

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.