I wish I spoke the language of inanimate objects. Think of the stories they could tell…

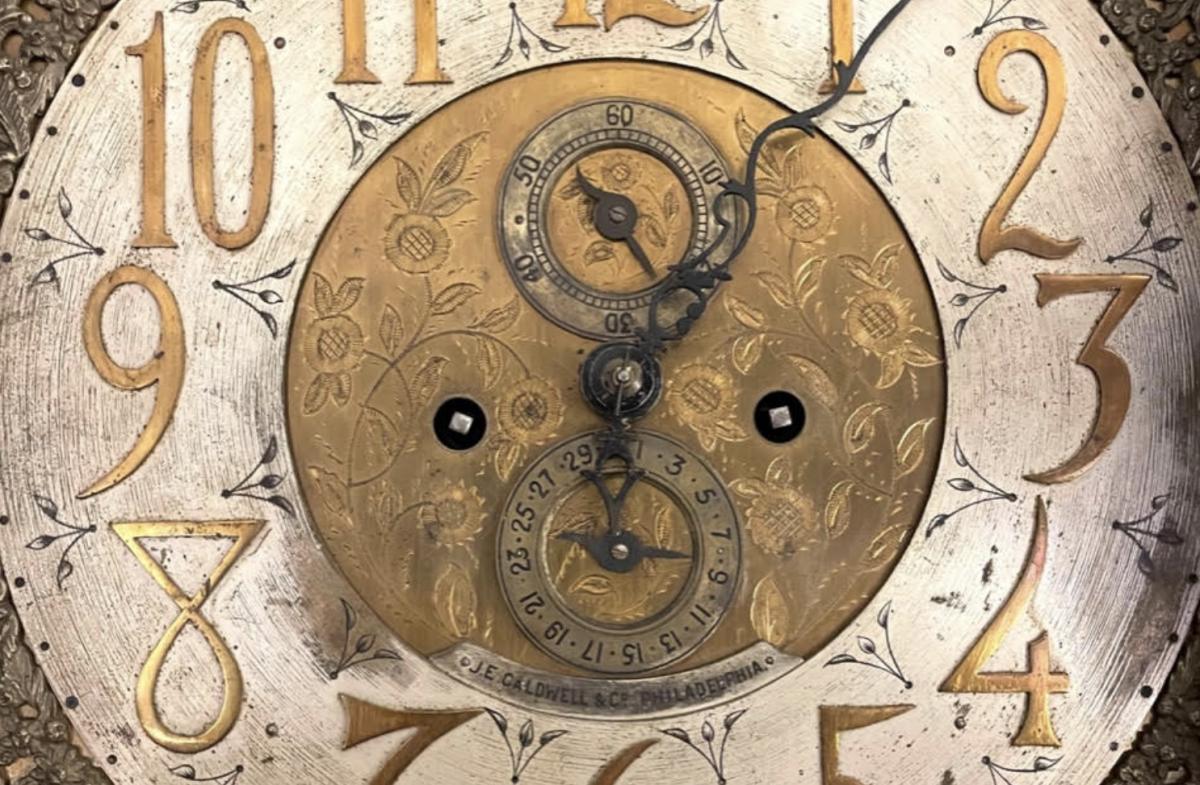

A grandfather clock stands in the corner of our living room, surrounded by a pile of the grandkids’ toys that have washed up against its sturdy base like sea foam along the tide line. It has been in that corner for the last thirty-plus years, but that’s only its most recent iteration. It originally came into the family as a wedding gift to “Gram” and “Pop,” my wife’s maternal grandparents, when they were married sometime around 1920. Crafted by the J.E. Caldwell & Co. in Philadelphia, the clock made its way to Washington, bundled coffin-like on top of a car, where it would steadily tick away the seconds of their lives, tolling the hours and the half-hours, day after day, year after year until Gram died in 1988. (Pop died in 1971.)

A grandfather clock stands in the corner of our living room, surrounded by a pile of the grandkids’ toys that have washed up against its sturdy base like sea foam along the tide line. It has been in that corner for the last thirty-plus years, but that’s only its most recent iteration. It originally came into the family as a wedding gift to “Gram” and “Pop,” my wife’s maternal grandparents, when they were married sometime around 1920. Crafted by the J.E. Caldwell & Co. in Philadelphia, the clock made its way to Washington, bundled coffin-like on top of a car, where it would steadily tick away the seconds of their lives, tolling the hours and the half-hours, day after day, year after year until Gram died in 1988. (Pop died in 1971.)

Even then, it still wasn’t ours. Gram’s original intention was that it should go to David, one of my wife’s older brothers. But at that time, David was living at the beach and it was deemed that salt air would not be conducive to the clock’s delicate inner workings or the cabinets fine finish. My wife volunteered to temporarily house the clock on her brother’s behalf, but David eventually moved to California and no one was willing to undertake the cost of shipping it across the country. But now David is gone, and so the clock remains here with us, looking over the shoulders of our own little lives.

The clock is a comfort to us on many levels. It reminds my wife of her beloved Gram and her brother David, self-appointed president of the Shenanigans Club. In the house in which I grew up in Pittsburgh, we, too, had a grandfather clock in the hallway, and so this one brings back memories of my own childhood back in Dreamtime. Its steady ticking soothes me during the day, and when I hear its sonorous chime in the middle of a dark night, I know where and who I am.

Oddly, grandfather clocks are by nature temperamental timekeepers. Maybe it’s because they have so many things to count: seconds, minutes, and hours; days of the week; phases of the moon. We’re content to let ours focus on one essential thing: keeping good time which it faithfully does with remarkable good and accurate grace. We can always look up at the sky to determine the phase of the moon.

Perhaps because I’m the tall one in our house, it has fallen to me—or perhaps I’ve just risen to the occasion—to wind the clock and keep it running smoothly. There are two pendulums—one for the timekeeping mechanism and one for the chime mechanism. I wind each once a week. My wife recently referred to me as the “steward of the clock,” a moniker of which I’m quite proud. Just as Robert Frost knew that one could do worse than be a swinger of birches, I’m perfectly content to be simply a steward of the clock. The job makes me a timekeeper, too.

I suppose that as one grows older, a clock’s gentle message of the flight of time grows ever louder. I like to write within ear-shot of our clock but I often get lost in my words and don’t hear the seconds flying past. At this stage of life, that’s probably a good thing; soon enough, everything will fall silent.

I wish I could speak the language of inanimate objects, specifically the dialect of our grandfather clock. Think of the stories it could tell…

I’ll be right back.

Jamie Kirkpatrick is a writer and photographer who lives in Chestertown. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Baltimore Sun, the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the Washington College Alumni Magazine, and American Cowboy Magazine. Two collections of his essays (“Musing Right Along” and “I’ll Be Right Back”) are available on Amazon. Jamie’s website is www.musingjamie.net.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.