Author’s Note: At middle age, I went on one of the most exciting outdoor adventures of my life. While I was there, the experience reminded me of a similar adventure I had done when I was going through my “quarter-life crisis” that I had kind of forgotten about. What did it mean to bounce these two trips off each other, to mirror one against the other? What had I learned, if anything, from then until now. It took me four years of writing this essay to find the story, to find and realize what these trips had taught me about myself and the ways life and age change us all.

From Hell’s Half-Mile to Powerhouse

No woman ever steps in the same river twice,

for it’s not the same river,

and she’s not the same woman.

—with thanks to Heraclitus, et al.

A COWBOY, a fireman, a fisheries biologist, two foresters, two botanists, three nurses, six guides, plus a naturalist and a writer, walk onto the rafts. This is no joke: From places near and far, we descended upon Idaho and chartered a backcountry plane to drop us off in the middle of the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness, the largest roadless area in the lower 48, to begin a six-day whitewater adventure on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River, one of the deepest gorges in North America.

With two years of angst and anxiety under my belt in anticipation of this trip, I choose one of the “leisure boats” with Neil and some others. The leisure boat is the “safe” boat in my mind, an oar raft where a very well-trained guide, to whom we are paying a hefty sum, does all the work of rowing and maneuvering and keeping us from harm, and we guests just sit on top, amid the luggage, equipment, and supplies, and enjoy the view, 2.3 million acres of jagged western wilderness.

Two years is a lot of time to know something is coming in advance and to think about it and worry about it and come up with all the ways injury and death could occur, or at least discomfort. Over the past twenty-four months, every time the river trip crossed my mind, my stomach lurched. Anytime it was mentioned aloud and a friend oohed and aahed over the opportunity I would have, all I could say was that I hoped to make it back alive. I was serious about that. I did not want to fall out of the raft into the icy water, hit my head on a rock, break an arm or a leg, get caught in a “window shade,” drown, or any of the other river catastrophes I’d heard about. I wanted adventure, but, at middle age, I wanted to come home unscathed.

Even though I’m on the leisure boat and we’ve had a brief safety training, I’m still nervous about some other unknowns, such as whether Neil and I will sleep well while camping. And what about the bathroom situation?—will we have enough time in the morning, with twenty-eight other people, to do our business? On the raft, will we be self-conscious of our bodies, not so tight and firm anymore?

And how will I fit into this crowd? We are with twenty of Neil’s old friends and their spouses from when he lived in Idaho thirty years ago working as a surveyor for the U.S. Forest Service. The group lucked out with a permit gained through a lottery system and organized the trip to reunite after one man’s newfound health after overcoming cancer, to celebrate recovery, retirements, and annual rebirth. At age forty-six, I am the youngest of this group of sixty-and seventy-somethings, and Neil’s retirement from teaching at a nature center is one year away. All these older folks seem joyful and free spirited and unafraid, and yet I’m still obsessing that this trip might be my last.

As we shove away from the launch site at Boundary Creek and start out bobbing under a cloudless sky of cerulean blue, I recite my mantra in my head: I will not fall out of the raft. I cannot find an unawkward strap to hold on to as we nearly immediately hit a series of rapids—Sulphur Slide, Ramshorn Rapid, Hell’s Half-Mile, Velvet Falls, and The Chutes—and one person on my raft, a retiree who spends half the year in Arizona and half in Mexico, somehow loses her balance and does a sort of half backflip over the side of the raft. Then she gracefully rewinds herself back in, a maneuver that resolves itself so fast that no one, including her, even knows how it happened. It is like a mirage. She doesn’t even get wet.

Before I know it, we’ve glided over a bunch of churning disturbances—rock gardens—with ease, no doubt due to the deft maneuvering on the part of the experienced guide, and the day begins to open for me; the crushing fear releases its hold a bit. I can see the churning ahead—the wide highway of slate gray, khaki green river, with occasional areas of bubbling white froth and peaks like sharks rising. Sometimes the water gets darker, a moonlight blue next to deep boulders; sometimes the canyon narrows, or an obstacle appears that agitates the water. And then the raft bounces and jostles over whatever’s underneath causing the riffles, and our bodies jiggle side to side, front to back—we have to allow ourselves a looseness of form, a sway of hips and spine, and go with the “river massage” when it’s offered—and we get splashed with icy buckets of snowmelt. But then, in a moment, the water is calm again, see-through to the bottom, covered in bowling-ball boulders.

The raft, I start to remember from a time long ago, with its air and loft, cushions the rapids. I don’t even come close to falling out in the first few hours. This expert guide team has run this river hundreds of times, scouting many of the three hundred rapids, memorizing each curve and eddy to perfection, knowing each drop during the 3,100 feet of descent and the one hundred tributaries that will join the Middle Fork along the way. I dare, for the first time in weeks or months, to let out my breath.

——

IN OUR FIRST DAY’S ORIENTATION, learning about river life and the types of rafts we can float on this trip, one of our guides, who wants us to revel in our good fortune of being here, tells us with dramatic emphasis and pauses that we are thirty of only ten thousand people in the world who will get to experience this river this year. Ten thousand seems like a lot of people to me, and I will be perplexed in days to come when we camp at well- worn beaches and in forests with clear human-made paths and established tent sites and see numerous other rafts and dozens of other people every day along the river—eco-groovy families and guided fishermen in dories—because these imprints of humans don’t jibe with my idea of wilderness.

It is upon first mention of this number of people that I recall my previous, and first, river trip, on the North Fork of the Koyukuk River in Alaska. We didn’t see another person in six days on the river, and groups (if there were any other than us) were not even allowed to travel with more than six people. We didn’t sign up for reserved campsites in advance; we floated up to whatever sandy or rocky beach we came across and set up camp whenever we wished, day or night, in the land of the midnight sun, leaving no trace of our fleeting habitation.

Up there, in Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve, above the Arctic Circle, only two thousand people visited the entire 8.4 million-acre park each year; our group of four participants and two instructor-guides saw only two people in eighteen days, passing them on foot during the backpacking portion of our trip, which was odd because there are no roads and no trails in the hummocks and scree fields of the Brooks Range.

I was twenty-five then, with only a few years of camping and backpacking experience, no river experience, no expectations, not much knowledge, and not much fear, entering a place where proficiency in wilderness skills was necessary for survival. I was an Alaskaphile, and the Outward-Bound trip was the best way I had figured out to get to see the inner sanctum of Alaska that few people ever visit. More importantly, it was the way I had decided to address what I called my “quarter-life crisis” and take stock of what I was doing with my life, whether the office job and corporate ladder track was where I wanted to be.

In August of that year, 1996, whitewater was sparse on the river; I would learn later that the North Fork of the Koyukuk was only a Class I and II river, not expected to have much more than ripples—and the water was low that summer, so low that our group had to paddle hard all day, every day, to get anywhere, blistering my hands and splitting my fingers into bloody canyons from the wetness and friction. I was unaccustomed to that kind of work. As I was the oldest participant on the trip and the only one with a job, one of the three nineteen-year-olds who were my trip- mates nicknamed me “Office Hands.”

I may be the only one with a job on this trip as well, self- employed with my multiple part-time gigs. But unlike the Outward-Bound adventure, whose mission was to change lives through challenge and discovery and for which I had hoped for self-reflection but gained none and to make lifelong friendships but did not, I’m not here in Idaho on this river with these people to learn anything about myself or to prove anything to myself or to change anything or to gain any new skills or necessarily to bond with anyone. I’m here on this mid-life river trip in Idaho in support of Neil and his friends, and it’s supposed to be for fun and relaxation and an abandonment of responsibilities and all life’s “shoulds”; to be taken care of, cooked for, and cleaned up after. I’m not looking back to the ghosts of lives I could have led; I’m not looking ahead to life’s next act.

With the Alaska memory sparked, my body begins to remember that it has already been on a river. It recalls the way the raft glides over a patch of silky water, slipping on top of a surface boulder and making no splash on the descent. It knows that the bubbles in the brewing beast only indicate the deepest water, not something more sinister; that the river points our best route forward with arrows of whitewater, nature’s subtle navigation signal; and that a jarring bounce off a boulder will send the raft into a backwards twirl. I begin to recognize the river like a home I once knew, a dream I once had, a meal prepared for me in a foreign land that waters my mouth once again.

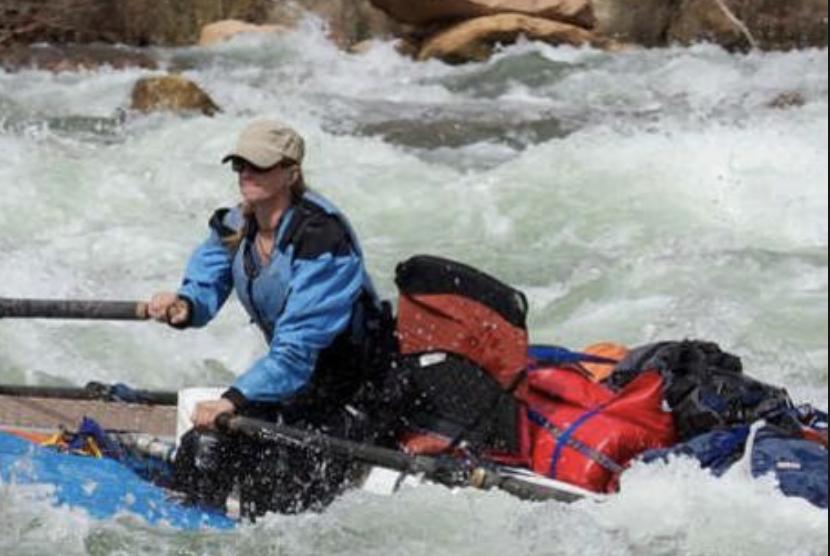

The snake of the river slices through tall, straight, and relatively young evergreen trees like lodgepole pine, covering the brown mountains around us like a porcupine, hour after hour. Though a significantly different landscape than my regular environment in Virginia, the high desert color palette is unending and unchanging. I feel like a dead twig watching the scenery go by, bored by the inactivity on the leisure boat, while our guides seem to be relishing the mystery and thrill of each new moment of “man versus river.” I start to consider that I have five more days of passive unengagement, and by the end of the day I decide I will become a more active participant and hop on the paddle boat instead, where a guide gives commands from the back to four to eight of us paddlers who make up the crew and do the work. After this single day on the river, I no longer fear the Class III (“medium”), and Class IV (“difficult”) rapids I had built up in my mind for more than seven hundred days, that torrent of water plunging a gradient steeper than the Colorado River traveling down the Grand Canyon. I don the Neoprene gloves I brought to prevent “office hands,” and I slide back into the rhythms of the river I remember.

——

IN ALASKA, there was no question that we would never fall into the water because there were no significant rapids. But before this Idaho trip, I had wondered, intensely, how people sitting with one butt cheek on the side edge of the raft, paddling through high and irregular waves, roiling waters, tight turns, and dangerous holes could possibly stay in the boat on a Class II – IV river.

I learn it on day two.

It’s a matter of weight, friction, and force. I jam my inside foot under a baffle that runs across the center of the raft, and I jam my outside foot under the side of the raft until I am stuck. Neither leg, really, is in the right plane with itself: my shins are at a wrong angle compared to my knees, and my thighs are also at a wrong angle compared to my knees, as well as compared to my ankles, hips, and torso. At the end of a paddling day, I’ll discover, the tendons, joints, ligaments, and fascia of my legs will have taken a beating without even having walked. And despite wearing neoprene booties inside my Keens, my toenails and skin become nasty from my feet sitting in cold water all day. But the essential miracle here, and what I hang onto is: with the feet tucked in as such, I do not seem to be able to fall out of the raft.

Thus, I find my groove. I test out paddling on the right side of the raft, find it awkward even as I am right-handed, and then discover my good side on the left. I find out too that attacking the shark fins of curling waves in whitewater with our paddles in a metronomic rhythm keeps us in the raft. What looks monstrous, I realize quickly, can be stabbed into submission by human force and the friction of plastic against water. In my green hard-hat helmet, as the parched brown dryness of the rugged, mountain landscape drifts by, I jab the boiling water with gusto that afternoon. Like in Alaska, where my survival and that of five others depended on each of us learning to play an active role, I am pleasantly confident in taking back some of the responsibility for my survival.

I settle into a spot as the second paddler on the left behind the fireman/paramedic who offers the group a variety of legal and illegal painkillers, smooth-talks the men and women alike with a conspiratory close-in lean, and who apparently earned the nickname “Hollywood” when he was young. He’s still thin and handsome, grey-haired now, and he knows how to set and keep a pace, which is what the guides tell him is his job as the foreman. I try to mimic him exactly. Lean forward with my whole upper body, dig in or spear the water with my paddle, pull back; lean forward, dig in, pull back. We paddle up to thirty strokes at a time upon the guide’s command: “forward,” “back,” or “drift.” One stab at a time, like the daily, weekly, annual, and lifelong journey navigating the river of life, aiming toward some shore, launching back into the waters, repeat.

In this way, we conquer Powerhouse Rapids, Artillery Rapids, Cannon Creek Rapids, and Pistol Creek Rapid, the sound of each preceding its presence, almost a spreading open of the river like a zipper as the whitewater unfurls around us and we pass through.

——

THE MIDDLE FORK OF THE SALMON is a 100-mile Wild and Scenic River, protected by Congress in 1968 in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which means it is a free-flowing river with no dams, and so water levels are dictated by nature, not by man. This status is a rare occurrence in the nation now. According to the nonprofit organization American Rivers, less than one percent of America’s rivers are wild and free. Instead, most are dammed for recreation, water storage, hydroelectric power, irrigation, and flood control. Here, in mid-July, the waters are considered to be at three-and-a-half feet, and we will travel on average sixteen miles a day over six days, whereas just a month ago in June, waters were at nine feet and the guides traveled the river in about two days due to the great volume and speed of the torrent.

The North Fork of the Koyukuk in Alaska is also a 100-mile Wild and Scenic River, but I didn’t know that then. On that trip, I was four years out of college, veering off the typical path already, taking a month off work with a plan to write about the journey, plunging myself into the outer reaches of my comfort zone for the first time. I literally had no map.

I had never hiked, camped, or backpacked without Neil or been without him in an outdoor adventure setting at all, having been raised as a city girl who never even learned how to ride a bike. He taught me everything I knew in the outdoors: survival, weather, maps, gear. I had been a follower in all of it, though, not a leader, not even a team player. I had never walked such a thin rope all by myself as in Alaska.

I thought the great life lessons of the trip would come from the deep connections I would form with people traveling the same path—literally by my side while doing all of the work of surviving in such a backcountry area, a grizzly-bear habitat, completely off the grid including sometimes without radio contact, without any tethers of human civilization, a situation that was wholly unfamiliar to me—as well as going through similar or forthcoming stages of life; people who understood me, who could help me see a path. But the instructors had placed me into the group of teens rather than the other group of thirty- and forty- year-olds. How was I supposed to learn anything about myself with kids who still had mom and dad cooking their meals back home and who were sent here by their parents, while I was a professional in the workforce, having worked for my own funds to attend this trip, with a soon-to-be-husband back home?

While I was teaching those teenagers how to make a cheese sauce with the last few ingredients we had left late in the trip, I was also backpacking with a pack that weighed about half my body weight, 70 pounds, traversing a scree field a thousand or more feet high on a path we created that was the width of our own boot prints, and navigating alone in my head the complicated mental challenges of a group leader with anger management issues, the physical demands of the journey, and what it was all supposed to teach me about myself.

Now in Idaho, a half a lifetime later, I notice I’m infinitely more adept at all the rituals that being a traveling caravan off the grid and on the river requires. And although Neil and I are here together, he decides to stay on the leisure boat, so we don’t spend the trip side by side. I choose to have my own separate experience. He takes two optional hikes that I decline on. I revel in the yoga circle our guides lead each morning, finding great comfort, joy, and empowerment in being among a familiar language from my practice back home, while he somehow manages to avoid it every day.

Perhaps I am at last recognizing the lessons of Alaska; for the first time since that trip twenty-two years ago and the first time in our marriage, I realize I have become my own person. I have, in fact, become—the same way a wild river runs its natural course when allowed to be undammed.

——

RUNNING THE RIVER STARTS TO SEEM LIKE OLD HAT, and I keep the same position on day three for the drop at Marble Creek Rapids, the drop and jog of Jackass Rapids, and the bend at Island and Riffle. I’m starting to feel pretty badass about my skill set, having remained in the boat so far, and so on day four, which the guides tell us offers the biggest whitewater yet, I am as hungry for the rapids as a wild dog.

The guides rise at 5:30 a.m. at the start of yet another bluebird day and set out the first breakfast—coffee, yogurt, oatmeal, and fruit—while getting the hot, made-to-order second breakfast underway—eggs, pancakes, bacon, and French toast— to fortify our day’s exertion. We clients shuffle around, having slept well enough and in a private-enough location of our choosing, packing up our own tent and personal things like we do every day, and the guides carry the tents, sleeping pads, drybags, kitchen gear, bathroom gear, and everything else down a treacherous slope to the river and load five boats. Their chores take at least five hours each morning. I appreciate this luxury because in Alaska, we Outward Bound students were the ones making breakfast, cleaning up camp, packing belongings, and loading the rafts, an ordeal that took three to four hours and was hard on the hands. Here, after all the loading, one oarsman or oarswoman takes off, captaining the “sweep,” a Huck-Finn-like freighter raft that carries all our “checked baggage” and camp and kitchen equipment to our next overnight place and sets it up there before we arrive.

We’ve been bath rooming now for four days, getting through it just fine. In Gates of the Arctic in Alaska, administered by the National Park Service, we were not allowed to put anything into the river: no cooking materials, no body oils, no body fluids or solids. We dug cat-holes in the woods for poop and toilet paper. We had to sing to ourselves to ward off grizzly bears. Here on the Middle Fork, within the Challis, Payette, and Salmon National Forests, managed by the U.S. Forest Service, we’ve been instructed to pee in the river, not on land, because with all the ten thousand people using the same lands, the soil and campsites would start to smell like urine. When we’re on land, men simply unzip and pee directly into the water; women squat at the edge strategically behind a wisp of plant. Or, if we pull over in our raft out of the current for a moment for a pee break, we may all simply hurl ourselves over the side of the raft, wade in the river up to our waists in our pants, and stare at each other across the raft as we pee into the water together in our clothes. All of us are totally used to this now, and it’s far easier than worrying about surviving a grizzly attack. At camp, the guides set up a glorified ammo can called the “groover” for pooping, in a spot set away from camp in the woods with a scenic view of the river. A separate pee bucket for nighttime use is set up in the bathroom-without-walls as well. Among all their other morning chores, the guides also collect and seal the groover and carry it onto the raft for disposal at the end of the journey, and they dump the pee bucket into the river.

Day four, with its icy white sky, unfolds with Tappan I, Tappan Falls, Tappan II, Tappan III, Aparejo Point Rapids, and Jack Creek Rapids: they range from quick steep drops into large holes, to Class IIIs to IVs that the guides have to get out of the boat and scout in advance, to a series of constricted drops over a half-mile stretch. The team on my boat is fairly solidified now: the fireman, me, and a cadre of 60+-year-old women who are fearless and inspiring, with not a judgmental one among them; women of all shapes and sizes and life experiences: kind, independent, fit, and full of joy—not broken by burdens, despite enduring many of life’s hardest trials. I didn’t come to the river to take inspiration from anyone, and yet these women begin forming a picture in my mind of what a later-life woman can look like, in strength and power, a model I have never even considered that I will need in my days ahead. I had not expected to fall into such easy camaraderie. To my great surprise, this spontaneous bond forms without effort, and our team—all of us who have chosen to be here, on this boat, paddling, fiercely attuned to the moment—attacks the water wordlessly like a fine-tuned machine.

It is on one of these rapids that, without warning, without dreading it, without planning, without intellectualizing, we come up fast on a large black boulder in the river. In a flash, our large, bulbous, steady, safe vessel that’s been so gentle and protective all week, absorbing all our potential breaks and bruises, veers up vertically on the right in a dramatic 45-degree angle: that perfect moment like in a cartoon when a character is suspended in air before falling. No one screams, no one loses a breath, no one’s stomach knots.

“Lean!” someone yells, and we enact a maneuver we were trained to do during the first day’s orientation to keep the boat from flipping when it rides up high on one side: Each of us physically stands up, lays forward, or otherwise springs from position in order to lean into that terrifying high side of the boat with our full body weight. And so, all the weight of our eight perfect, imperfect, forgiving, forgiven selves rise up against the forces of gravity trying to take us down, trying to flip that boat and land us all in the churning water in the middle of a chute.

The moment is over in an instant. The boat lowers itself as if it had no intention of becoming upside down, and we paddle away like that’s what we were born to do. We end our day— dry—at Little Pine Camp with a meal of antipasto, lasagna, sausages, Caesar salad, and tiramisu, cooked up by our jubilant yogi-poet-chef guides whose gentle lessons in the ways of the river have taught me to trust.

——

THE SKY MOVES UP THE CANYON WALL now as we descend into a deep, dark cut of Idaho batholith: the Impassable Canyon, named during the Sheepeater Indian War of 1879 with the Shoshone-Bannock Tuka-Deka people who lived there, when the U.S. Army could no longer find a way to pass through the river’s canyon on horseback. Tall black rock rises up around us, and the river narrows. Here, in this chasm of earth, I feel very remote, indeed.

Even the sun can’t find us this deep. No watercolor-sunsets at Tumble Creek Camp on our last night, but we are surrounded by the orange glow of ponderosa pines. A campfire brightens the evening, and we snarf down our pistachio- and date-encrusted brie plate, our grilled Brussels sprouts with cherries and apples, the rosemary lemon chicken and cheesy polenta, our still-cold- and-fresh salad from one of the giant coolers kept aboard the sweep, our carrot cake, our beer, and our huckleberry-vodka- with-lemon cocktails. Cowboys and foresters dress up in lingerie from the costume bag that’s been unleashed for this last hurrah. Men and women paint their toenails in rainbow colors. Neil puts on a wig. I don a tutu and Mardi-Gras-bead headdress. And Karyn the geriatric nurse drapes her substantial bra-less bosom over the heads of the twenty-something year old menfolk guides seated on camp chairs, as a parting gift of love. We dance around the firelight, and most of the group drinks into the wee hours.

I make my way to the tent by myself in the dark while Neil stays up with the group. Whereas in Alaska, the landscape was so quiet and empty that I never even heard a bird song and I craved community with others, here on this last night, I want to take a little space, a moment to be quiet, to listen, to read, to reflect. My internal landscape wants to absorb and remember the external landscape: alive, authentic, simple, and free.

The next day, the Middle Fork ends at the main Salmon River, just as the North Fork of the Koyukuk terminated at the Middle Fork of the Koyukuk—both river trips of my life beginning at the origin of the river and ending at the terminus, like complete narrative stories with beginnings, middles, and ends, in and of themselves. The guides tell me this arrangement is not typical for raft trips, which usually cover a small segment of a very long river where you see no beginning and no end. We travel two hours by school bus on crude dirt forest roads, and eventually hop on a turbulent hour-and-a-half backcountry flight, which soars 10,000 feet over the river canyon that had been our home for nearly a week, back to McCall, Idaho, where Neil used to live and work in the forest with this very crowd. We hug goodbye to these good people, check into our hotel room, and ride out the bliss of river life for another few days.

For weeks and months before signing up for this trip and paying the high fees, Neil and I hemmed and hawed about whether we should go. We debated and discussed, rehashing all the same issues over and over, both of us terrible at decision-making, each one wanting to please and not overburden the other. Finally, after many sleepless nights, I said to Neil: It comes down to this. What we are deciding is what kind of people we want to be, or what kind of people we are: The kind of people who take the opportunity to have the trip of a lifetime, with all its risks and uncertainties, ups and downs, and potential for life-changing rewards; or the kind of people who don’t.

Now that it’s all over and we are back to our normal lives, remembering our wild and free days on the river in that remote, faraway place that, truly, so few people in the world will ever know, it is a relief and a revelation to me that we chose to go.

I’d been on a river before, and what I did in Alaska was in many ways a riskier trip, more remote, more at stake. I didn’t know that then because I had the confidence and ignorance of a younger person. On the last day in the Brooks Range in Alaska, we heard the news that a lawyer from Washington DC had been mauled and killed by a grizzly bear in the same corridor we’d been traveling. We had not seen more than a mud print of a grizzly bear track, had spent the eighteen days in Alaska in virtual wildlife-silence. But it could have just as easily been one of us. It could have been me. During that Alaska trip, the first of many steps I would take to steer away from a traditional work and family life, I had been badass before I even knew what badass was.

Did the wild and scenic rivers of my life teach me anything after all?

Yes, they did: Possibility.

I asked the river to intoxicate me once, as the poet Baudelaire suggested, and it grudgingly nourished me with the gift of inner strength. And then I allowed the river to intoxicate me again, soothing me with its endless rolling song, like the wind, the wave, the star, the bird. And in doing so, I found, thrillingly, that when I dared to take the leap into the wide-open unknown once again, the river rose up to meet me.

♦

Sue Eisenfeld’s essays have been listed five times among “Notable Essays” in The Best American Essays. From Arlington, Virginia, she writes about nature, travel, adventure, history, and culture. She is the author of Wandering Dixie: Dispatches from the Lost Jewish South and Shenandoah: A Story of Conservation and Betrayal. Website: www.sueeisenfeld.com.

Delmarva Review publishes compelling new nonfiction, fiction, and poetry selected annually from thousands of submissions worldwide. Financial support for the nonprofit literary journal is from tax-deductible contributions, sales, and a grant from the Talbot Arts Council with funds from the Maryland State Arts Council. Website: DelmarvaReview.org.

# # #

An eye-opening account of two trips that each held separate yet meaningful lessons about life for the author but also joined to meld her experiences into an inner knowledge of self. Beautiful descriptions of her surroundings both on the rivers and off. I was totally enthralled with details,sounds,emotions,and thoughts as Sue experienced them at 25 and at 50. Thought-provoking, touching and revealing. Loved this essay!