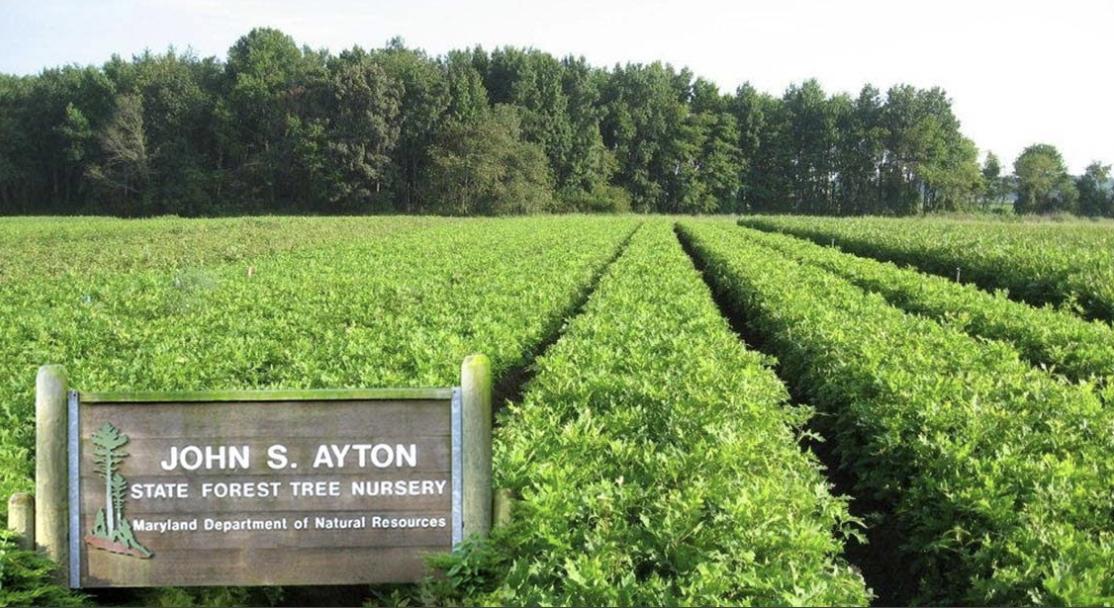

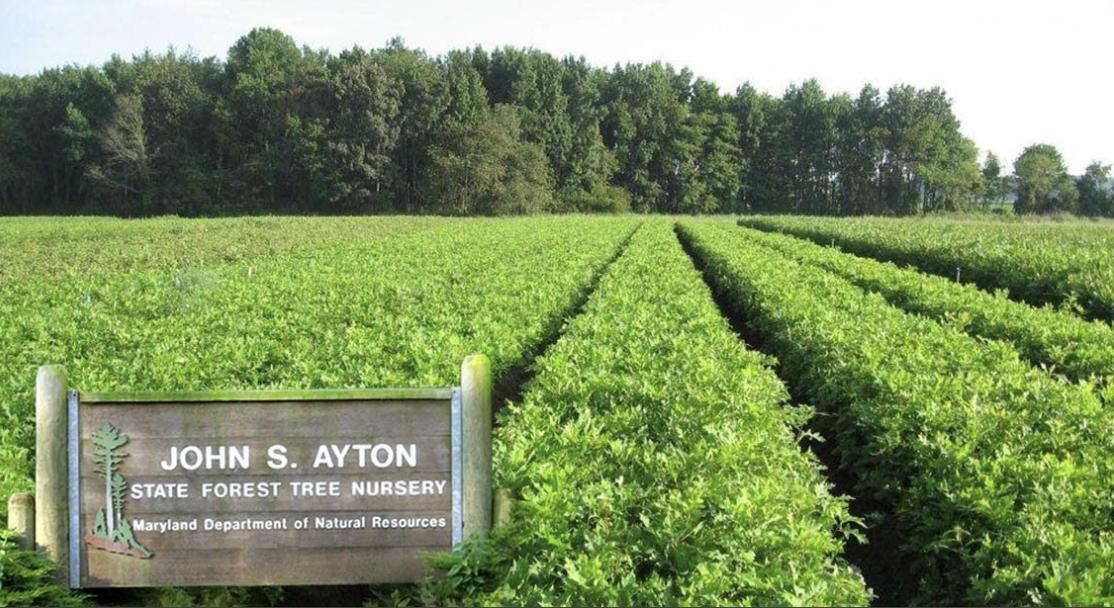

The John S. Ayton State Forest Tree Nursery in Preston will play a big role in helping Maryland meet is mandate to plant 5 million new trees by 2030. Maryland Department of Natural Resources photo.

Growing up in West Baltimore, Greg Burks never thought much about the lack of vegetation around him. But his younger brother suffered from asthma, and that was one of the family’s primary concerns.

“This is your brother’s inhaler,” Burks recalls his mother saying every time the boys went out to play. “Keep it with you.”

Only now does Burks realize that one of the reasons his brother needed an inhaler was that the level of ozone and other pollutants in their neighborhood was so high because there were so few trees around.

Now, Burks is poised to help families in Baltimore and other Maryland urban areas who struggle with their breathing because of air pollution. He manages the new Urban Tree Program for the Chesapeake Bay Trust, a nonprofit launched by state government in the 1980s dedicated to improving the watersheds of the Chesapeake Bay, Maryland Coastal Bays, and Youghiogheny River in Western Maryland. The trust’s mission is to plant 500,000 trees in urban areas over the next eight years.

“Marylanders’ lives depend on it,” Burks said in an interview. “That’s why this program exists. It’s for people who don’t have the resources to leave the city.”

Burks and his colleagues at the CBT are a small but important part of Maryland’s attempts to plant 5 million trees by 2030. That ambitious goal was set in legislation that the General Assembly passed in 2021, and it’s now up to a pastiche of state agencies, nonprofits, industry and environmental groups to make it happen.

On the one hand, it’s a bureaucratic process as all state government attempts to comply with new laws inevitably are. But on the other hand, it’s fused with optimism and imagination, and a sense that almost anything’s possible.

“If we can green our cities, we can improve our lifespan,” said Burks’ boss, Jana Davis, the president of the Chesapeake Bay Trust. “This isn’t just about science. This isn’t just about the environment. This is about human health.”

And while it may be a bit of a stretch to say so, some stakeholders believe the state’s execution of the tree planting law could be a template for how the government implements the Climate Solutions Now Act of 2022, the ambitious legislation that passed this year to reduce carbon emissions in Maryland by 60% by 2031 and hit net-zero carbon emissions by 2045.

At a minimum, said Suzanne Dorsey, the assistant secretary of the Maryland Department of the Environment, who is helping to oversee the implementation of the tree planting measure, it can serve as a way of tracking the state’s ability to meet the provisions in the new climate laws.

“It’s about counting and accounting,” she said. “I think the new legislation will require us to track more and to do more.”

Throughout the country — indeed, throughout the world — there is a campaign to plant as many trees as possible as a key ingredient to combating climate change. One nonprofit, called 1T.org, aims to see 1 trillion trees planted worldwide over the next several years. The organization has already received commitments from major corporations around the world to plant 33 billion trees, and now the advocacy group is turning its attention to states like Maryland.

The Tree Solutions Now Act passed in 2021. A less ambitious forest conservation bill, sponsored by state Del. Jim Gilchrist (D-Montgomery), passed overwhelmingly in the House last year, but when it landed in the Senate, the Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee, which was wrestling with the larger climate legislation, amended the House measure to put the 5 million tree planting requirement into law, and that’s how it emerged from the General Assembly.

The amended legislation called for 500,000 trees to be planted in urban areas, and an additional 4.5 million would be planted as part of a process known as aforestation — establishing a forest on land not previously forested.

The legislation required the state to assemble a stakeholder group to figure out how to implement the law. It makes tens of millions of dollars available for initial tree inventories and purchasing. And it laid out specific tasks for various state agencies and other organizations.

“Five million trees is a lot of trees,” Dorsey said.

The Commission for the Innovation and Advancement of Carbon Markets and Sustainable Tree Plantings began meeting earlier this year. Its membership, spelled out in the legislation, features representatives of the Maryland Department of the Environment; the University of Maryland College Park; the Maryland Commission on Environmental Justice and Sustainable Communities; the Maryland Farm Bureau; the Maryland Association of Counties; the Maryland Municipal League; and three environmental groups: Blue Water Baltimore, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, the Maryland League of Conservation Voters, the Nature Conservancy, and the Patapsco Heritage Greenway.

Serving as ex-officio members: representatives of the State Treasurer’s office; the Maryland Department of Agriculture; the Maryland Department of Natural Resources; and the Maryland Forestry Foundation.

Beyond counting on the Chesapeake Bay Trust to oversee the planting of 500,000 trees in urban areas, the legislation spells out discreet roles for most of the state agencies: The Department of Natural Resources, which operates a tree nursery on the Eastern Shore, and the Agriculture department are responsible for most of the rest of the tree planting and will work with groups and local governments across the state to achieve that goal. MDOT is responsible for tree maintenance along state highways and for replacing whatever trees are removed for road construction. The Environment department is responsible for coordinating it all.

“I want to emphasize what a great collaboration this has been so far,” Dorsey said.

‘A game changer’

Several stakeholders praise the Chesapeake Bay Trust’s early planning for the new law, which will enable the nonprofit to begin handing out grants to other entities for tree planting as soon as state funds become available on July 1.

The irony is, trust leaders weren’t part of the early planning for the tree planting legislation.

“It was not our idea,” Davis said. “It’s the brainchild of other folks. But it’s an honor to be part of the process.”

As soon as they learned they were included in the bill, trust leaders mobilized to get ready, she said. “We knew if we didn’t start early we’d never be ready for the fall 2022 planting season.”

One of the first things they did was bring on Burks, the West Baltimore native who had worked for other nonprofits and institutions — most recently for Johns Hopkins University as a senior community programs manager focused on affordable housing, the digital divide and food deserts. He had never worked in the environmental space before.

Burks, who calls the urban tree planting program “a game changer,” convened a series of listening sessions around the city and state, to determine how to bring communities together, how best to implement the tree planting program, how to maintain the trees once they’ve been planted, and how to access civic resources.

“Greg Burks is a force of nature and a delight to work with,” Dorsey said.

The Chesapeake Bay Trust has already been sifting through dozens of grant applications from groups that want to plant trees. Some are seeking funding to plant just a few; others have the capacity to plant 10,000 trees in a fairly short time period. The applicants range from local governments and forestry boards to nonprofits to schools, churches and community associations.

The trust will have $10 million in tree planting grants to dole out this year — and has already received $14 million in spending requests. Davis said one of the things trust leaders like about the program is that it lets local leaders who know their communities best chart their own tree planting and maintenance strategies.

“The community interest in this program has been incredible — way larger than we thought,” she said. “Which speaks to the real community need.”

Other agencies are preparing to implement the law in different ways. The Department of Natural Resources has hired 12 tree planters and one assistant nursery manager.

And state agencies are putting private Maryland nurseries on alert that they’re going to have to increase their stock of saplings. Nurseries are among the biggest parts of the state’s agricultural sector.

“They’ve got to know that we’re about to order a lot more trees than we usually do,” Dorsey said.

Some local governments already have tree planting programs under way.

Baltimore County, for example, has had an unofficial goal of maintaining a 50% tree canopy for several years, and in an interview, County Executive John A. Olszewski Jr. (D) said the number has gone up during his administration thanks to a handful of tree planting initiatives, including a new one called the ReTree program, which focuses on urban and poorer communities in the county

The county government traditionally gives hundreds of trees away to residents on Arbor Day, and it makes free backyard trees available to property owners whose lots are one-tenth of an acre or bigger, Olszewski said. But the ReTree program relies on data the county is already using for environmental justice and equity initiatives to plot out where the heat islands are in the county and where trees are needed the most.

“We’re really being more intentional about it,” he said.

The tree plantings started a few months ago in Dundalk and will expand over the next several weeks into Essex, Owings Mills and Randallstown. About 1,000 trees will be planted this year through the new program.

The idea of using statistical analysis for a tree planting strategy “is surprisingly new,” Olszewski said. “We know the imperative of the environmental justice movement, and this aligns it with the data.”

David V. Lykens, the Baltimore County director of Environmental Protection and Sustainability, is the Maryland Association of Counties designee on the state’s new tree commission, and Olszewski said Lykens will discuss the counties’ successes on the tree planting front with others on the panel.

“We think we have a story to tell,” he said.

‘It’s wonky’

Even with so many stakeholders involved with implementing the state’s new tree planting law, there are sure to be some skeptics.

Colby Ferguson, director of government and public relations at the Maryland Farm Bureau, is a member of the tree commission and a supporter of the 5 million tree goal generally.

“It’s an interesting discussion,” he said. “I’m always trying to figure out what we’re trying to do here and what we’re not.”

For farmers, Ferguson said, the issue is how and where the 5 million trees will be planted, and what kind of acreage of arable land will be involved.

“We don’t want to be trading our prime farmland and our food for environmental practices,” he said. “We can’t trade food for carbon sequestration.”

That’s just one of the many questions the state tree commission is going to try to answer in the months ahead. The panel is supposed to issue a written report to the General Assembly this fall, outlining how the state can hit the 5 million tree mark by 2030. Members of the commission aren’t just looking into how to plant them and making sure the right tree species are going into the appropriate areas. They’re also figuring out how to maintain them and how to prevent invasive vines, which are becoming increasingly prevalent in Maryland, from overcoming them.

State officials are also going to keep track of how many trees are being planted, because so many entities — and even individual landowners who may plant a single tree — are going to be involved. They have to figure out how to count the carbon mitigation when the trees are all planted and as they mature. And they have also been directed by the tree planting legislation to set up a Maryland-based carbon offset market.

Carbon offset markets are just being established around the country. They enable businesses, including power plants, to purchase vouchers when they are unable to meet short-term carbon reduction goals. while they transition to more sustainable business practices. The money spent on carbon offsets are traditionally put toward emission reduction projects — including the planting of a new forest.

So the challenge for Maryland officials is figuring out what kind of entities might want to purchase carbon offsets from the state that match the emissions reductions from all the new trees. And they’ve also got to determine how much revenue a carbon market can generate and how much of that they can plow into additional tree plantings.

“It’s wonky,” said Dorsey, the Department of the Environment assistant secretary, who is slated to become deputy secretary on June 1. “This market is new and volatile. People are just getting into it.”

Earlier this month, the state tree commission met virtually to discuss the offset market. It was a challenging discussion, with technical terms like “MS4 acres of credit,” “additionality” and “ease of access into the market” being thrown around liberally.

“Some of you are as wonky as we are or maybe even more in the weeds, and some of you, your heads may really be spinning,” Dorsey conceded.

Maryland officials believe any offset market they set up based on the tree program can become a national model. But Anne Hairston-Strang, acting director of the Maryland Forest Service, laid out a warning about the limits of the carbon offset markets that almost anyone could understand.

“The prices we’re seeing in the carbon market aren’t going to fund aforestation,” she said. “So we’re going to have to look for additional funding.”

By Josh Kurtz

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.