Alison Saar (b.1956 Los Angeles) is the daughter of artists. Her father Richard Saar was a coast guard combat artist, painter, and art conservator. During high school, Alison helped her father restore Egyptian, Pre-Columbian, and African art. Her mother Betye Saar is a prominent African-American artist whose assemblages and collage art are known and collected by museums and connoisseurs world-wide. Art and history were part of Alison’s upbringing. She graduated from Scripps College in 1978 with a double BA degree in art history and studio. She received her MA in 1981 from Otis College of Art and Design ins Los Angeles.

Saar’s work is strongly influenced by her studies of the culture of African and African-American peoples, with an emphasis on the role of black women. Her work reflects her interest in gender, race, and her personal experiences. Her early works are hand-carved, life-sized wood sculptures, including “Snake Charmer” (1985) (Hirschhorn Museum, Washington, D.C.), and a 15’ tall commissioned bronze sculpture titled “Monument to the Great Northern Migration” (1994) (Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, Chicago).

“Strange Fruit” (1995) (tin alloy, dirt, wood, found objects, rope, paint) (Baltimore Museum of Art) is named after the 1939 Billie Holiday song “Strange Fruit”: “Southern trees bear a strange fruit, blood on the leaves and blood on the root. Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze; strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.”

Rather than the expected male figure, “Strange Fruit” depicts a nude female with noticeably red lips. She hangs upside down by a rope tied around her ankles. She is the strange fruit. The niche in her abdomen resembles the key hole of a door. Sealed in the niche are found objects. Several African cultures carve niches in the abdomen of their male figures and fill them with powerful objects that are capable of healing, settling disputes, punishing evil, and keeping the peace. Saar’s niche, filled with unknown found objects, is a signature feature shared with her mother’s art. There is a key hole, but no key, suggesting something of value is locked inside.

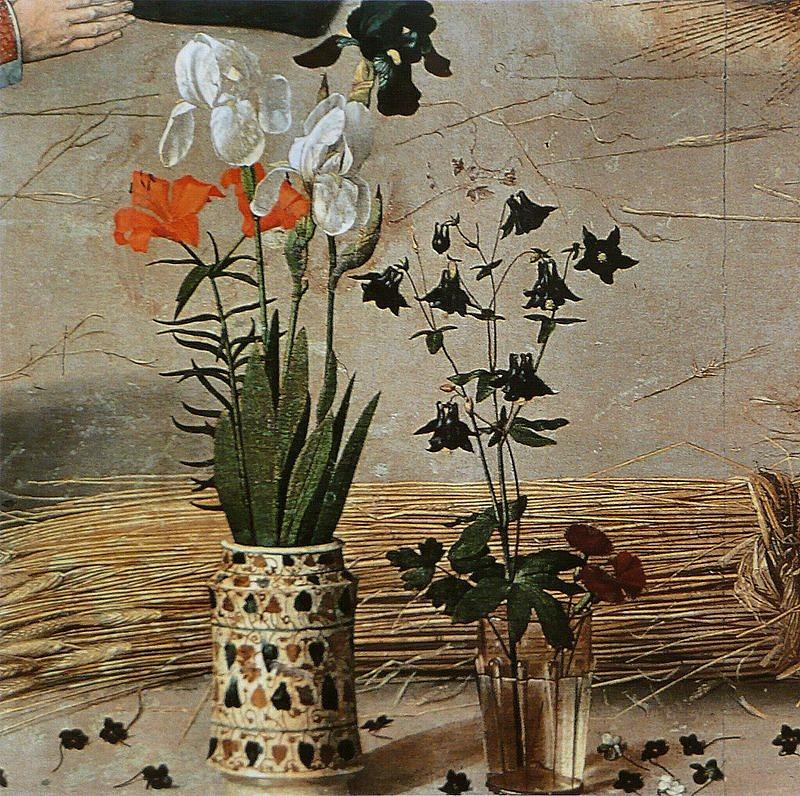

Beyond the reference to American slavery and ancient African customs, “Strange Fruit” contains a significant reference to art history. The pose of the figure, while upside down, is the pose of Venus in Botticelli’s painting “Birth of Venus” (1485). American history, art history, and African history are combined in her piece. Saar asks the viewer to contemplate the human experience, while creating a haunting and mysterious presence.

“Swing Low” (2008) (13’ bronze standing on Chinese granite) was commissioned for the Harriet Tubman Memorial, located on the traffic island on West 122nd St and Frederick Douglass Drive, in Harlem. Tubman is depicted as a determined figure who strides forward with purpose. Saar describes her vision: “What I wanted to do was depict outwardly her inward spirit of compassion, and her fearlessness…this unstoppable locomotive…because despite all these efforts and bounties on her, she managed to continue her work…That’s sort of where the train-like image of her petticoat came from…I intentionally had her facing south. The community largely saw it as the figure not facing the direction of the Underground Railroad, which was north-bound. But for Harriet Tubman it was a two-way street, going back and forth, and that’s how I wanted to remember her.”

Saar created a pattern on Tubman’s long skirt to resemble West African passport masks, small masks (1-3’’) that are considered sacred objects. They are carried about the person, and they are used in special ceremonies and rituals. To Saar, these masks represent the slaves who were saved by Tubman on the Underground Railroad. Tubman’s skirt also has roots that grow from the earth and attach to it. Symbolic of the roots of slavery, they are pulled out of the past and out of the ground as the slave moves to freedom.

Square carvings placed around the granite base of the statue depict stories of Tubman’s life. These alternate with traditional American quilt pattern designs.

“Embodied” (2015) (14’ x 6.5’) (bronze) is located on the lawn of the Hall of Justice in downtown Los Angeles. Rather than the traditional scales of justice and a sword, the female figure holds an open book of the law in her right hand. She is a tall, slender woman with a presence and stature that allow her to hold the open book out to the viewer, and to balance it. Her left arm is raised, and perched on it is the dove of peace. Her serene face combines several ethnic features: almond eyes, broad nose, high cheekbones, and full lips that are characteristics of the diverse population of Los Angeles.

Saar adorns the statue’s dress with 200 words that reflect the meaning of justice in more than a dozen of languages. The words were collected from the staffs of the Los Angeles County Sheriff and District Attorney. Saar also solicited from the public and students’ words that they believed embodied the spirit of justice.

The statue has exceptionally long braids. One braid is draped over her arm and the other falls down her back. Braiding is the method used to make thin grasses into thick ropes. Saar states, “The braid is a universal symbol of unification, by the twining of different entities to achieve a greater strength.”

“Imbue” (2021) (12’ bronze) (Pomona College, Claremont, California) was made for a Saar retrospective. Saar depicts the Yoruba goddess Yemoja, goddess of childbirth and all bodies of water, protector of pregnant women, child safety, feminine mysteries, love, and healing. The goddess has a special meaning for Saar: “Yemoja crops up in my work a lot. I first discovered her when I was living in New York in the 1990s, trying to grapple with being a young mother and having a career–it felt like a real balancing act…I see Yemoja as not only helping me in terms of patience and balance and child rearing but also as a watery, life-giving spirit who nourishes my creative process.” Saar depicts Yemoja as a strong woman who balances several types of water containers on her head, and pours water from a bucket onto the earth. “A lot of my life has been a balancing act between anger and a kind of serenity, and that’s also reflected in my process,” says Saar. The goddess Yemoja came to America with African slaves. She remains a figure of worship in Africa, the Americas, Cuba, and Brazil.

Alison Saar is a prolific artist. She continues to carve sculptures for exhibitions and large public commissions. She also is a prolific printmaker. Always conscious of current events, she created “Rise” (2020) (8.5’’ x 11’’) (linoleum print) to honor the Black Lives Matter movement. Her inspiration for the image came from studying photographs of women from the Black Panther movement. Prominent among them was the raised fist gesture, and she updated the Afro hairstyle. She chose the print media and the small size for “Rise” because they made the work more accessible and affordable. All the profits from the sale of the prints were donated to three Los Angeles community organizations.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.