St Nicholas of Myra (270-343 CE) (Greece) and the numerous miracles he performed were the inspiration for St Nicholas Day celebrated on December 3, 2020. He was buried in the Church of St Nicholas in Myra. The great schism (1054) officially separated the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches. The Byzantine Empire was conquered in 1087 by the Seljuk Turks who brought the religion of Islam. A group of Italian Catholic merchants in Myra secretly removed the bones of St Nicholas from the Church and took them to the Italian town of Bari. They bones were interred in the Basilica of San Nichola and remain there still. The first Crusade (1096) departed from Bari, and St Nicholas’s miracles involving the saving of people, particularly seafarers, became popular with the Crusaders. On their return from the Holy Land, the Crusaders spread the cult of St. Nicholas in Europe. By the Fifteenth Century stories had evolved to include St Nicholas the gift giver and patron saint of children. Children all over Europe celebrated St Nicholas Day and left shoes or stockings by the fire; if they were good children, they would receive a gift, if not, they might receive a switch.

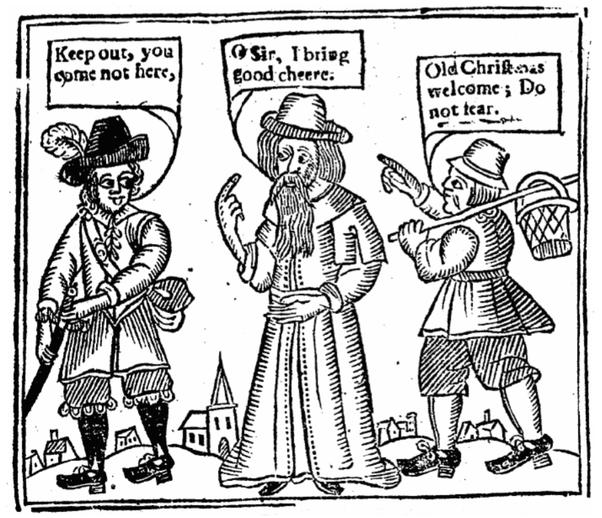

St Nicholas Day suffered a setback in Germany when Martin Luther (1483-1546) stated that Christmas Day, December 25, was the appropriate time for gift giving to celebrate the Christ Child, Christkind in German. In England, Oliver Cromwell (1647) declared Christmas was a “Popish” tradition and punished those who observed Christmas on December 25. He promoted the idea that Christmas really was derived from the Roman pagan festival of Saturnalia. The people revolted. In 1652, “The Vindication of Christmas, O Sir I bring good cheer to Pilgrims, ”an anonymous print was circulated. A Puritan on the left is about to draw his sword while Old Father Christmas, dressed in a long gown similar to the robes of St Nicholas, calms the Puritan, and a commoner welcomes Old Christmas.

Josiah King’s pamphlet “The Examination and Tryall of Old Father Christmas” (1658) depicts a white haired and bearded Father Christmas, this time in Bishop’s robe and mitre, similar to the early images of St Christopher. He wears a long fur stole, and although he is in prison, he sits in a chair with a nailed leather back and curved arm. Accused by the Commonwealth of idleness, drunkenness, profligacy and other debaucheries, Father Christmas was not restored to his proper role until 1600, when Charles II came to the throne

From their arrival n America, Puritan colonists banned Christmas in the Massachusetts Bay Colony until 1681. It was Dutch immigrants in New Amsterdam that brought the stories and legends to New York. On St Nicholas Day in Holland, seafaring men went to the harbor to take part in church services for St Nicholas. On their way home they would pick up small gifts, such as oranges imported from Spain, to put in the stockings or shoes of children. Coincidentally, St Nicholas often was shown with three golden balls representing the gift he gave to the father of three daughters for their dowry. The oranges represent the golden balls. Alexander Anderson’s engraving for the New York Historical Society’s annual meeting in 1810 officially recognizes the first “Festival of St Nicholas on December 6, 1810”. St Nicholas is depicted in traditional bishop’s robes and on the hearth a Dutch teakettle, waffles, cat, and stockings. On the mantle, the good little girl holds several gifts in her arms, and her stocking overflows. The bad little boy holds a switch and his stocking is full of switches as well.

A small paperback book titled The Children’s Friend: A New-Year’s Present, to the Little Ones from Five to Twelve was published in 1821 by William Gilley in New York. The book included eight illustrations of the poem “Old Santa Claus with much delight,” that tells of Santa Claus’s visit on Christmas Eve, December 24, not December 6. Riding in a sleigh pulled by a reindeer, Santa wears the red robe associated with a bishop. In other illustrations for the poem he is depicted as tall and thin, quietly putting toys in stockings hung on the children’s bed post.

Another contributor the image of Santa Claus was Washington Irving (1783-1859). Famous for his novels “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle,” he wrote under the assumed name of Diedrich Knickerbocker, a satire titled A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty (1809). In the story Irving described Sinter Klaas as a rascal in a blue three cornered hat, a red waistcoat, and yellow stockings. The figure of Santa Claus was by this time a jolly heavy man who smoked a traditional Dutch long white clay pipe. He rode over the roof tops in a horse drawn wag and dropped the children’s gifts down the chimney.

A poem called “A Visit from Saint Nicholas”, known familiarly as “The Night before Christmas,” was published anonymously in the Troy Sentinel, on December 24, 1823. The author, disputably, Clement Moore, was a Biblical scholar, a professor and a poet, who taught at the Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church in New York City, did not admit to authorship of the poem for twenty-two years. The poem contributed a number of new details about Santa Claus. He was dressed all in fur, with a broad face and a little round belly, and he filled the stockings hung by the fire. Moore’s unique contribution to the Santa Claus image was the names and number of eight reindeer: Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donner and Blitzen. Moore presented a peaceful vision of the arrival of Santa Claus in contrast to the more traditional public festivities of drinking, eating, carousing and general rowdiness as the revelers ran riot in the town. Santa Claus became a family centered figure, and as Moore put it, “A wink of his eye and a twist of his head soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread.”

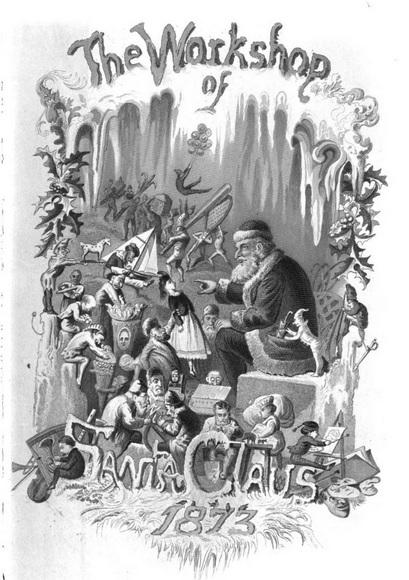

Louisa May Alcott, of Little Women fame, wrote in 1856 a poem titled “Christmas Elves,” which would have made another addition to the story of Santa Claus if her publisher had decided to use it. However, in 1857, Harpers’ Weekly published a poem titled “The Wonders of Santa Claus” that included these verses: “He keeps a great many elves at work, All working with all their might, to make a million of pretty things, Cakes, sugarplums and toys, To fill the stockings, hung up you know, By the little girls and boys.” Godey’s Lady’s Book, (Christmas 1873) contained the image “The Workshop of Santa Claus.” Numerous elves sew, hammer and otherwise busily make toys. The caption reads: “Here we have an idea of the preparations that are made to supply the young folks with toys at Christmas time.” The same issue also contained an article by a socially conscious writer who informed the reader that contemporary toymakers were not elves, but real people, mostly struggling foreigners. “Whole villages engage in the work, and the contractors every week in the year go round to gather together the six day’s work and pay for it.”

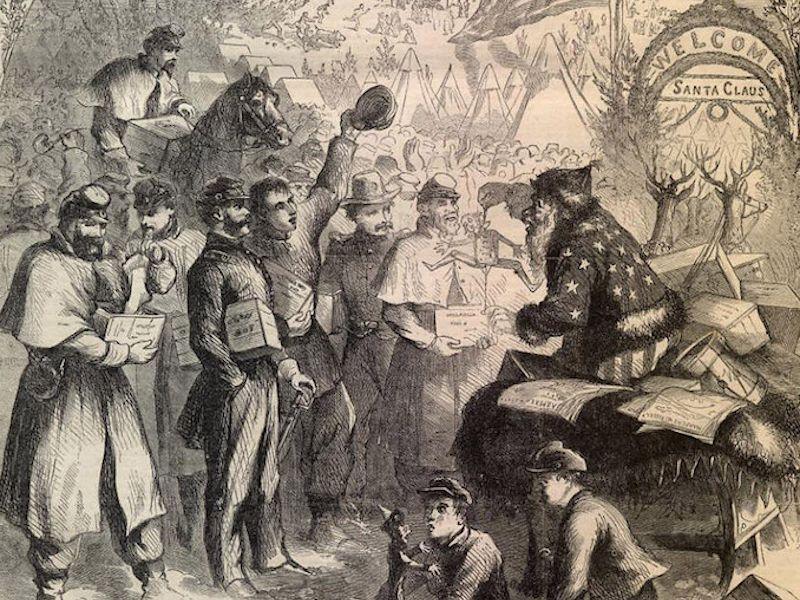

The artist who most influenced the evolving image of Santa Claus was Thomas Nast, an immigrant from Bavaria and a famous political cartoonist. Nast, inspired by his German background and “The Night before Christmas,” created what was to become the iconic image of Santa Claus. However his first depiction of Santa Claus, published by Harper’s Weekly (1863), drawn and printed during the American Civil War, was not what one would expect. “Santa Claus at the Union Camp” depicts a white bearded Santa dressed in a jacket with white stars and pants with white stripes. Although a black and white image, the intended reading of the red, white and blue of the American flag is obvious. This patriotic Santa passes out gifts to Union troops. A strong Union supporter, Nast included a small boy holding a puppet with a noose around its neck that looks very much like Jefferson Davis.

Thomas Nast continued to draw images of Santa Claus for Harper’s Weekly for the next thirty years, completing thirty-three Santa’s. The iconic image is “Merry Old Santa Claus” (1881). His red suit, arm-load of toys, pack on his back, white beard, smiling jolly face, and a long stemmed pipe, this Santa composed the model for all Santa’s to follow. One more part of the story came from Thomas Nast. He began noting “Santa Claussville, N.P.” in the corner of his works, to identify the North Pole as Santa’s home.

After the end of the Nineteenth Century, Santa Claus’s image was secure. Writers such as Frank Baum, commercial companies such as Montgomery Ward and Coca Cola, and song writers and singers such as John Marks and Gene Autrey continue to add delightful bits of information about Santa Claus. St Nicholas from Myra, Kris Kringle or Kristkind from Germany, Old Father Christmas from England, and Sinterklaas from Holland, all participated in bringing Santa Claus to America.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.