What gets to me the most is the In Memorial displays propped on three easels by the front door as I enter the ballroom. Matted individual photographs from my high school yearbook show that 42 of us have died and too many have died young.

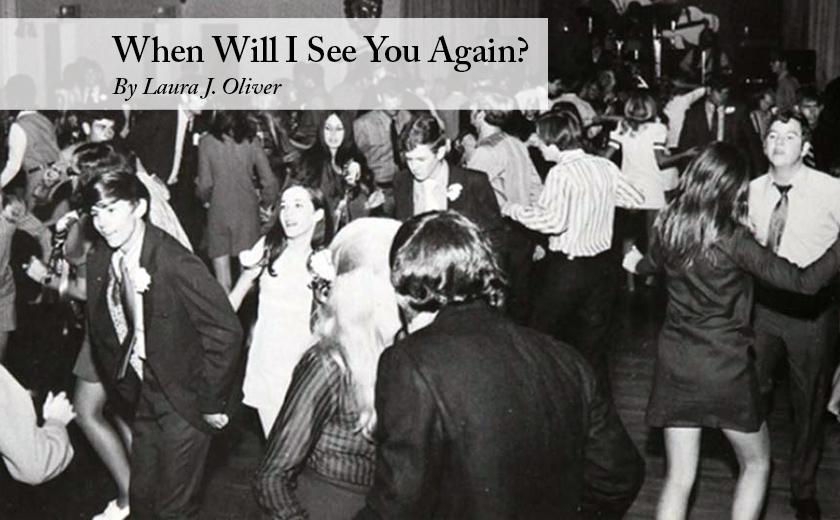

I’m at a high school reunion tonight, decades after having parted company with every single person in this room. No one in my life now was in my life then, although this room is full of people with whom I entered first grade. The first boy to kiss me is supposedly here tonight. We were 14. I required coaching from my best friend to get him to make his move. I scan the room and see a tall, lanky figure holding a beer.

Who put the moves on whom, Billy O’Brien?

And my senior year boyfriend is here as well. Traveled all the way from Brooklyn for this event. He is funny, kind and has grown even more handsome. His presence is a gift, and he brings a gift: flowers.

Our committee chairman opens the reunion with a prayer as we are milling around, and this feels a bit uncomfortable. I comply instinctively as the good-girl, rule-abider I was, then remember that’s not so much me anymore and look up over a sea of bowed heads to catch the eye of others who feel self-conscious opening this secular event with a religious ritual.

Over the decades since we have seen each other we have all changed in more than just looks. In this case, our reunion organizer has adopted the happy confidence of a late-night comedienne and the instructional skills of a kindergarten teacher. She makes us practice raising one hand while simultaneously covering our mouths with the other upon a signal that she is going to speak. It’s like we’re learning a trick and there’s going to be a prize until we figure out it’s crowd control and the rebellious teens we are at heart, start talking over her microphone. “You’ve got detention,” I say to the classmate next to me. “You’re suspended,” she says in return.

This reunion is a chance for a new perspective on the past. We were hormonal, insecure, and so angsty, it was hard to be present in high school. I want the opportunity to pay attention. To meet people I used to know for the first time. To see how everyone’s lives have turned out.

But I do exactly what I did in high school!!! I hang out selectively with those I know best! Is it possible we haven’t changed at all?

On the memorial easels there is a photo of my best friend. She was academically brilliant and a gifted musician. After college, she married an eccentric guy who made his living selling Kirby vacuum cleaners but who annually piloted a small plane to their family reunions in the Midwest. On the way back from a gathering in which she had not flown with him, the plane went down over the Great Lakes. His body was never found, leaving Diane in a no man’s land of unprovable widowhood with two small kids.

I was giving a craft talk one evening perhaps 20 years ago to a bunch of writers—it had been publicized in the newspaper–when I looked up and saw Diane sitting unobtrusively in the back row. Afterwards, I went out into the hall to find her, and she told me she was dying. Cancer. I think she would have slipped out without speaking had I not stopped her, and I understand why. My immediate impulse was to hold open a door she had come to quietly close.

Margie Milligan’s photo smiles from the easel as well, sweet, with kind eyes, forever 17. She contracted mononucleosis our senior year. I’d had it, several of us had. But Margie suffered the rare complication of a ruptured spleen and died. I was the recipient of a scholarship created in her name though Margie had been a quiet girl I barely knew. I hadn’t even realized until this moment how utterly beautiful she had been. There are so many other classmates pictured on these displays tonight. They are all beautiful.

It’s autumn in Maryland. The wild crab apple trees are wearing ruby-orange bittersweet in their boughs. The ballroom doors are open and a waxing moon, two days from full, is on the rise over the water. After several hours of visiting the past, dinner on a paper plate, and a dance, I’m ready to leave.

I tell Diane’s photo that I love her, and that I hope she is here somehow. And I tell Margie Milligan I’m sorry she was deprived of a future, and I thank her for abetting mine. I tell her how lovely she is and that I wish I had known her.

Would you live forever if you could? Genetic engineers are researching the possibility that aging might be treatable, like an illness. Through tweaks to the immune system and DNA repair mechanisms, we might someday enjoy perpetual youth.

I’m studying the photos on these easels and suddenly the idea of living forever feels as wrong as being gone too soon. Why is that? If I were sick, I’d want to be well and if I were dying, I’d want many, many more years. But would I want forever? Would you?

I think I’d be disappointed if death could be exchanged for an eternity here. More of same, while in many ways appealing, would be to relinquish knowing what else there is, what’s on the other side of now. Walking to my car under the mercy of the moon, I know I don’t want to be held back. I’d rather graduate into the mystery of what’s to come.

And to believe this will not be our last reunion

Laura J. Oliver is an award-winning developmental book editor and writing coach, who has taught writing at the University of Maryland and St. John’s College. She is the author of The Story Within (Penguin Random House). Co-creator of The Writing Intensive at St. John’s College, she is the recipient of a Maryland State Arts Council Individual Artist Award in Fiction, an Anne Arundel County Arts Council Literary Arts Award winner, a two-time Glimmer Train Short Fiction finalist, and her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her website can be found here.