You don’t expect a garbage bag in Easton’s dormant downtown storefront windows to be the reminder of a major museum exhibition, but that’s exactly the point. People walked by, puzzled. “Is it an antique shop? What is this?” For the Academy Art Museum’s Executive Director Charlotte Potter Kasic, the bag wasn’t trash. It was a playful nod to Robert Rauschenberg.

“Our team has had fun with the downtown ‘takeover.’ The windows have continued to evolve, and we’ve been going in and changing things each week.” For her, that storefront prop is an easy entry point to the man himself—a way of saying that he used everyday objects on purpose, making art people recognized.

But most people walking past Easton’s storefront windows have no idea that this was Rauschenberg’s language—or that he has a real connection to this area. And that is why the Museum is opening Rauschenberg 100: New Connections on December 11, an exhibition that will remain on view through May 3, 2026 and place Easton right in the middle of his worldwide centennial celebration.

Robert Rauschenberg

“Do you know who Robert Rauschenberg is?” Kasic asked as we began talking. “It’s interesting. A lot of people in our community do not understand what a powerful artist, change-maker, and influencer he was.”

“Rauschenberg was an incredible sculptor, artist, collaborator, printmaker—and, turns out, photographer,” she said. “He was one of those essential culture makers at Black Mountain College. He worked with John Cage. He worked with Merce Cunningham. He and Jasper Johns were lovers. He had a marriage and a son. He was a really interesting guy.”

His work, she said, grew out of a desire to re-ground abstract expressionism into things people recognized. “He wanted to make everyday art for the everyday person. Things had gotten so abstract people didn’t understand it anymore.”

From there, Kasic shifted to what the exhibit means for the Museum itself. “One of the things I’ve been saying about our identity is that, to do good things, there has to be a trinity. We need to be honest with our origin story—founded by artists, for artists. We need regional specificity, and we need excellence.”

And that’s when the local connection comes into focus.

Rauschenberg worked closely with artist, art historian, and master printmaker Donald Saff, known for his collaborations with Roy Lichtenstein, James Turrell, and others. After an illustrious career at the University of South Florida, Saff moved to Talbot County and continued working with these major artists at Saff Tech Arts, his studio in Oxford. “Rauschenberg was making this work right here in Talbot County, which is insane to me,” Kasic said.

That history leads directly to the centerpiece of the show: Chinese Summerhall, the hundred-foot-long color photograph Rauschenberg made during a 1982 trip to China.

“It was a cultural exchange,” Kasic said. “He was trying to mend the woes of society through understanding one another through art. And that also happens to be very timely right now.”

Apparently, Rauschenberg isn’t new to the Museum; they’ve had pieces connected to this project for years. Their Rauschenbergs include more than twenty related works—test prints, studies, and editions that show how the project developed. “Our work is really only interesting when you realize in context that, yes, they’re limited editions in their own right, but really it was all leading up to this monumental piece,” she said.

Bringing that piece to Easton, however, was not simple. There are only four of the hundred-foot works in existence: one at the Guggenheim, one in Florida, one with the Rauschenberg Foundation, and one at the National Gallery.

“We went to the University of South Florida, because that’s where it was made,” she said. “They agreed to loan it to us. We were full ahead for the show. And then the main contact person suddenly no longer worked there, and the loan fell through.”

That changed the entire exhibition plan. “Without the 100-footer, this story falls flat,” she said. “Everything was leading to that.”

Curator-at-large Lee Glazer then stepped in. “Lee wouldn’t take no for an answer,” Kasic said. “She went to the Rauschenberg Foundation and told them, ‘Our loan just fell through, and the National Gallery and the Guggenheim said no. Will you loan us yours?’ So it was like our last chance. And she got it.”

And that’s how the rarely exhibited photograph will now be seen in Easton. It documents Rauschenberg’s first journey to China and his creative partnership with Saff.

Another piece of the exhibit is the documentary the Museum commissioned, featuring local Talbot residents Saff and George Holzer, walking through how Chinese Summerhall came to be—starting with Saff nervously driving Rauschenberg around Tampa and getting lost.

“I finally got up enough nerve and said, ‘Would you consider working with me?’” Saff says in the film. He then recalls Rauschenberg rejecting the fine French art paper Saff offered and choosing the custodians’ garbage bags instead. (Which makes the Easton storefront prop feel very on point.)

The film moves from those small moments into the larger story: the China trip—the scrolls, the colors, the fifty rolls of film—and finally the darkroom marathon, where five enlargers were moved by hand to build the image eight to ten feet at a time. “All it took was one exposure to be off on one enlarger, and it’s trash,” Holzer says. “We were down to the last chance.” And time was tight: the work was due at the Leo Castelli Gallery on New Year’s Eve.

Eventually, they ran it through the processor and hoped.

It worked.

The film ends with Saff’s move to the Eastern Shore and to a small building on Oxford Road, where, as one voice in the film puts it, “artists make the dreams of other artists come alive.”

The film is only part of the experience. Around the exhibition, the Museum is offering what Kasic describes as “a lot of different ways to engage with it over time.”

There will be classes inspired by Rauschenberg’s techniques, including China ink painting on Xuan paper; a performance of John Cage’s music; mixed-media workshops; a lecture by Don Saff; and a February 21 talk by Rauschenberg’s son, photographer Chris Rauschenberg.

There is also a strong community component tied to sponsorship.

Those who join by December 1 receive tickets to the VIP preview party on December 10, the first official unveiling of the exhibition. They’ll also be entered to win a signed Rauschenberg print from the same series, made with Saff, along with access to private programs, behind-the-scenes events, and the exhibition publication.

It won’t end there. The Museum’s Spring Gala will serve as the closing celebration of the show. “The whole gala is going to be Rauschenberg-themed,” Kasic said.

As we wrapped up, Kasic underscored what she’d love to see. “I hope everybody brings their whole family here,” she said. “Between Christmas and New Year’s—when everybody’s in town and feeling like we’ve stared at each other enough—now let’s get out of the house. I want them to come to the Museum. We’re free. We’re open to the public.”

“I’m so proud of this show,” she said.

Since it’s his birthday, I thought Rauschenberg should have the last word. In the film, he’s asked why he kept pushing himself into new places and collaborations. This is how he responded: “I want my work to make you proud of yourself and make you care about the world and everything that is in it. I care. I care. I’m paying the world back for having been born. That’s my rent.”

A hundred years on, the sentiment still holds.

For more info:

https://academyartmuseum.org/rauschenberg-100-new-connections/

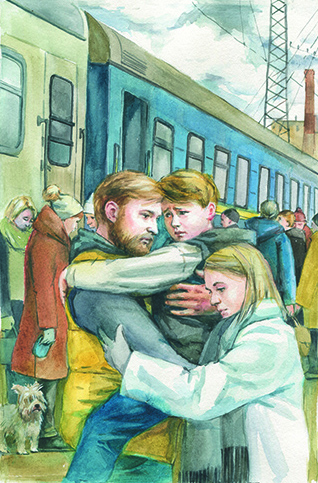

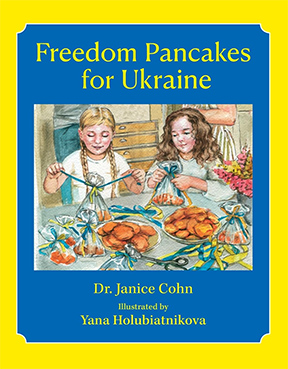

I came to know Yana that spring, after the Russian occupation ended, when I was contracted to design a children’s book raising awareness and support for Ukraine. As part of the agreement, I was to help select a Ukrainian artist to create more than a dozen color illustrations for the manuscript by Dr. Janice Cohn, a children’s book author and psychotherapist. Janice, a donor to the Ukraine Children’s Action Project (UCAP), contacted the organization’s co-founder, Dr. Irwin Redlener to see if they could recommend a Ukrainian artist. She was then put in touch with UCAP’s Regional Director, Yuliia Kardash, who spent many hours researching artists who might be suitable for the project, and finally recommended Yana. After reviewing Yana’s work, Janice and I agreed she was the perfect choice. Our correspondence began soon after.

I came to know Yana that spring, after the Russian occupation ended, when I was contracted to design a children’s book raising awareness and support for Ukraine. As part of the agreement, I was to help select a Ukrainian artist to create more than a dozen color illustrations for the manuscript by Dr. Janice Cohn, a children’s book author and psychotherapist. Janice, a donor to the Ukraine Children’s Action Project (UCAP), contacted the organization’s co-founder, Dr. Irwin Redlener to see if they could recommend a Ukrainian artist. She was then put in touch with UCAP’s Regional Director, Yuliia Kardash, who spent many hours researching artists who might be suitable for the project, and finally recommended Yana. After reviewing Yana’s work, Janice and I agreed she was the perfect choice. Our correspondence began soon after.

Since neither of us spoke the other’s language, Yana and I labored through a translation app to agree on how each illustration would appear using both her innate artistic intuition and scene requirements (complex positioning of multiple people, expression, etc.) on our part. And, for all I knew, despite cross-checking, a word in the Ukrainian app expressing “joy” could have been slang for “potato.” But she was kind, and rather than pointing out a translation problem simply asked for clarification. Some of the illustrations would take several more versions.

Since neither of us spoke the other’s language, Yana and I labored through a translation app to agree on how each illustration would appear using both her innate artistic intuition and scene requirements (complex positioning of multiple people, expression, etc.) on our part. And, for all I knew, despite cross-checking, a word in the Ukrainian app expressing “joy” could have been slang for “potato.” But she was kind, and rather than pointing out a translation problem simply asked for clarification. Some of the illustrations would take several more versions. Janice’s new narrative grew out of her “conviction that kindness and compassion can steady children in even the darkest times, and that in helping others, we often find our own resilience.” The book became a parallel story about two children, a boy, Artem, escaping Ukraine with his mother, and a girl, Hannah, in America who became determined to raise funds for the war-torn country. Chapters became counterpoint narratives about each child’s experience.

Janice’s new narrative grew out of her “conviction that kindness and compassion can steady children in even the darkest times, and that in helping others, we often find our own resilience.” The book became a parallel story about two children, a boy, Artem, escaping Ukraine with his mother, and a girl, Hannah, in America who became determined to raise funds for the war-torn country. Chapters became counterpoint narratives about each child’s experience. For Janice, the book became more than a story—it became a reminder that even small acts of care can repair the world. Yana eventually received some copies of the book.

For Janice, the book became more than a story—it became a reminder that even small acts of care can repair the world. Yana eventually received some copies of the book.