I first met Bob Day in Miss D’s coffee shop beneath the dining hall on the Washington College campus. It was 1970 and the 60s weren’t over. The war in Vietnam spread to Cambodia, and the Beatles broke up.

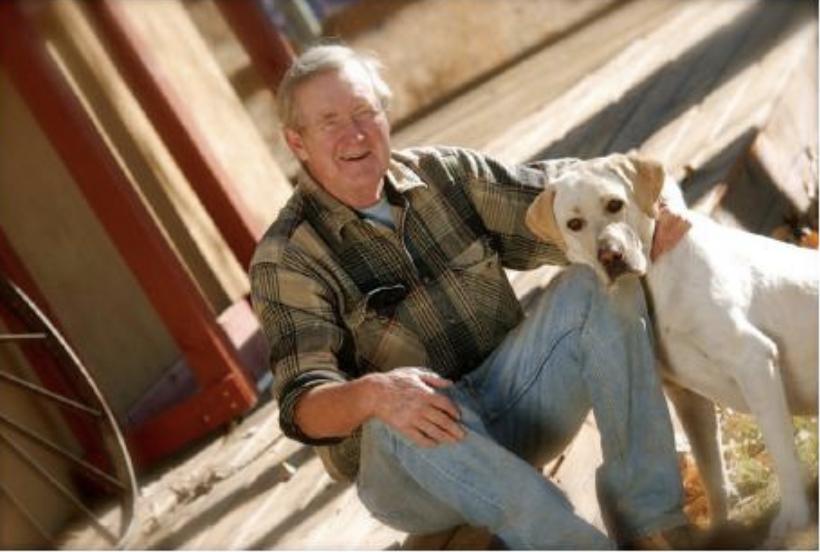

Bob was slouched in a booth with a few students and wore his famous cowboy boots. I believe it was just before he began his official role as creative writing professor in the English Department, maybe even the day of his interview with Dr. Norman James, Chair of the English Department. I don’t recall the conversation, but I’d bet by the end of it we knew more about Lawrence and Hays, Kansas than we did about Annapolis and more about Vladimir Nabokov and poet William Stafford than we ever would about John Milton and Chaucer. And that was just over cokes.

Bob was slouched in a booth with a few students and wore his famous cowboy boots. I believe it was just before he began his official role as creative writing professor in the English Department, maybe even the day of his interview with Dr. Norman James, Chair of the English Department. I don’t recall the conversation, but I’d bet by the end of it we knew more about Lawrence and Hays, Kansas than we did about Annapolis and more about Vladimir Nabokov and poet William Stafford than we ever would about John Milton and Chaucer. And that was just over cokes.

Suddenly, our literary landscape had been altered. Contemporary literature came teeming across our transom like the cattle drives Bob wrote about. Toto was wrong. Knowing Bob Day was to be forever in Kansas, although a meta-Kansas he inhabited and brought to us in his writing, that intersection of place and imagination.

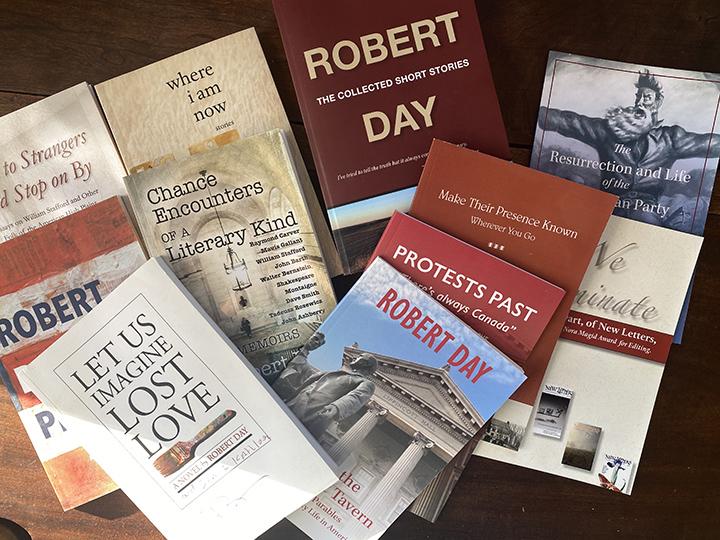

Poet Richard Hugo wrote about the importance of “place” as he argued against the creative writing workshop bylaw that writers should only “write what you know.” Hugo believed that writers should use towns as points of entry into the realm of the imagination and should take emotional ownership of an imagined town rather than the actual place where “the imagination cannot free itself to seek the unknowns.” Bob’s Kansas, from his The Last Cattle Drive to his last Collected Works, is more akin to a state dreamed by Voltaire’s Candide, sometimes edited by David Sedaris, other times by Raymond Carver. He was wry without being cynical, alternately rhapsodic and terse, and a storyteller of the first order in print and in life.

Anthony Burgess said about The Last Cattle Drive, “…his novel is like the man himself—ebullient, precise, Rabelaisian, witty.” True enough.

I knew Bob as my writing teacher for the last two years of my college life. It didn’t take long to be caught up in the physics of his momentum and mission to make Washington College a kind of mothership for writers, to both instruct young writers and to bring published authors to read on campus.

He was as instructive outside the classroom as well, which led to many animated evenings at The Tavern and countless anecdotes about the literati. Somewhere between Faulkner and Joyce, he would tell a story about a cat-lady in Ludell, Kansas. I can’t remember if that was instructive or not, or even if she was real. He had an encyclopedic memory of literature and biography, along with a childlike glee telling his many ribald shaggy-dog stories, the ones he didn’t write. In fact, for twenty years, his phone calls to me would begin with “A nun and a porcupine walked into a bar…” I would often wince but knew it was a prologue to greater things.

Bob was a connector, a conductor of literary events, and a master of introductions. When he brought the poet David Ray to the campus, there wasn’t even an available space for the reading—it was held in a biology classroom. Then came Diane Wakoski and William Stafford, and dozens of some of the finest writers in the world who took the time to engage with writing students. For a long time, the walls of the Rose O’Neill Literary House were covered with broadsides announcing those events.

And then there were the literary sojourns. “Mr. Dissette, send three poems to Miller Williams c/o the University of Richmond. We’re going down there in 8 days.” He was always formal when he gave us instructions, less so at The Tavern. So, of course, I did and went and ended up drinking a bottle of wine with Anthony Burgess on a screened summer porch where we talked about Dylan Thomas and his struggle writing Enderby.

Each of Bob’s students has stories of this sort. Those kinds of spontaneous and cryptic inclusions continued throughout his life. Just six years ago, he called. “Mr. Dissette, pack a change of clothes, coat, and tie. We’re going to Kansas City to honor Bob Stewart’s PEN Nomination for Editing. Stewart was the longtime editor of the prestigious New Letters and BkMk Press. Decades later, I’d learned not to decline these bizarre orders. So, his wife, Kathy Day, and I flew to Kansas City, Missouri—Bob drove, and I never asked why—for the dinner honoring Robert Stewart. Once again, I made good friends, which led to introductions to other writers and even connected long-lost associations: David Ray had been editor of New Letters before Stewart. With Bob Day one thing always led to another.

Each of Bob’s students has stories of this sort. Those kinds of spontaneous and cryptic inclusions continued throughout his life. Just six years ago, he called. “Mr. Dissette, pack a change of clothes, coat, and tie. We’re going to Kansas City to honor Bob Stewart’s PEN Nomination for Editing. Stewart was the longtime editor of the prestigious New Letters and BkMk Press. Decades later, I’d learned not to decline these bizarre orders. So, his wife, Kathy Day, and I flew to Kansas City, Missouri—Bob drove, and I never asked why—for the dinner honoring Robert Stewart. Once again, I made good friends, which led to introductions to other writers and even connected long-lost associations: David Ray had been editor of New Letters before Stewart. With Bob Day one thing always led to another.

I lost track of Bob during my life on the west coast, although I remember a directive that came to me via postcard in 1979. “Write to Miller Williams (again!) at Arkansas. Go there as soon as you can.” I did consider his ‘advice’ and looked into it. The writing program at U of Arkansas at that time was on fire, but classes were filled for the year. Plan B was studying with Cherokee poet Ralph Salisbury at the U of Oregon in Eugene.

Of course, it was during the twenty-something years I was away that Bob Day gave one of his greatest gifts to Washington College: the Rose O’Neill Literary House and Press on Washington Avenue. One of Bob’s cardinal traits was as a deal-maker. He was a natural-born horse-trader, and if you were ever engaged in one of his conspiratorial transactions you walked away wondering what repercussions might be in the offing. He was constantly pushing beyond the academic comfort zone to further the cause.

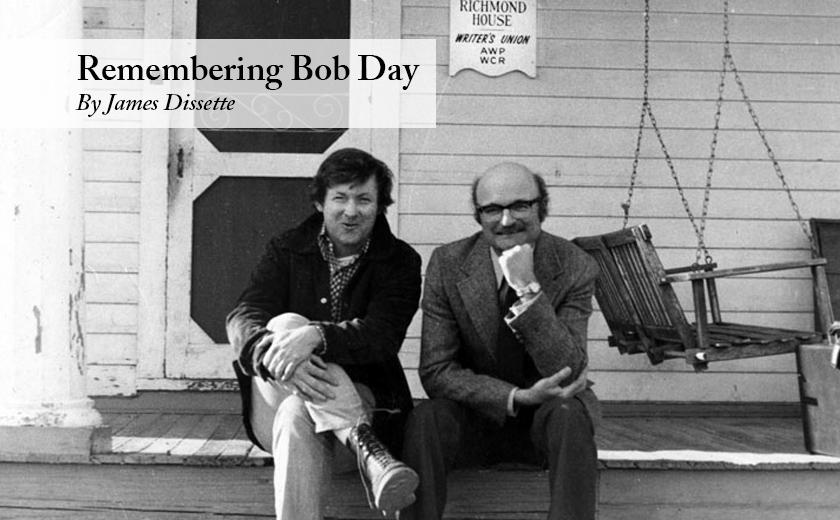

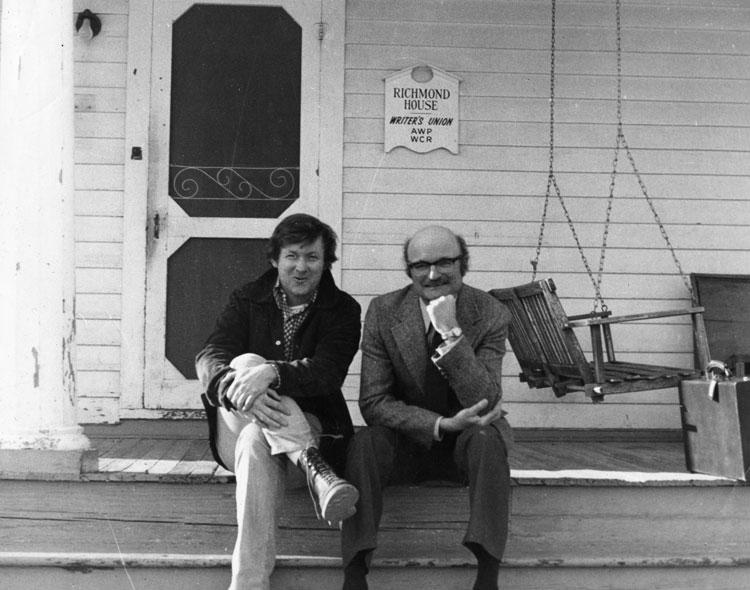

Bob conceived the idea of having a “literary house” two years before I left in 1973 with a ramshackle old building next to the WC Maintenance building. It should have been demolished—a bathtub even fell through the floor—but instead became home to the newly formed Writers Union, Associated Writing Program (AWP) and to wayward writing students embracing the dry rot and springless couches as a creative sanctuary and bell jar hermetically sealed with the spit of William Carlos Williams, Jane Austen, and Charles Dickens.

After a second incarnation—Dorchester House—another literary enclave, Bob in 1985 orchestrated the purchase of the house on Washington Ave. and became its founding director. Soon, he would add a press, another stroke of his genius, that continues to operate today as a teaching press and sometimes publisher of limited-edition books.

One story exemplifies Bob’s eternal quest to make Washington College the home of a creative writing center of the highest order:

. . .

Bob wrote, “The students wanted Toni Morrison. I doubted we could afford her but didn’t say so. I told them I’d check it out, which I did through a contact I had at her publishing house: her fee was beyond our reach. Enter President Douglass Cater who, full disclosure, was always something of an unindicted co-conspirator to my Literary House schemes. When I told him the problem, he suggested we not offer her money, but an award.

“What award?” I asked.

“The Washington College Literary Award,” he said.

“We don’t have a Washington College Literary Award.”

“Then we’ll make it,” he said.

And he did. We offered the first Washington College Literary Award to Toni Morrison and—again, at President Cater’s suggestion—created a scholarship in her honor. She dropped her fee, came to campus, met the student who would get the scholarship, gave a reading, had lunch with students, and accepted the award, which was a letterpress broadside excerpt from her novel Beloved. Students of literary history will discover Toni Morrison’s vita lists The Washington College Literary Award along with the Nobel Prize she got the following year.”

. . .

Toni Morrison was in good company. Dozens of writers answered Bob’s invitations: James Dickey, Allen Ginsberg, Anthony Burgess, Edward Albee, Richard Wilbur, Gwendolyn Brooks, and a list too long to appear here.

When I returned to Chestertown in 2002, Bob and I picked up our old friendship, but with new roles. I was to design his books, an effort that brought us together frequently in town or at dinner with his wife Kathy on their porch overlooking Still Pond Creek.

Looking back on it, I’m convinced that Bob thought I was eternally near starvation or without funds enough for rent, an assessment occasionally not without merit. He provided me with countless book design jobs, his own and others. His last large endeavors were Let Us Imagine Lost Love, For Not Finding You, and Collected Works. With each project, he rounded up previous students of his who had become editors and writers to help with edits: Kathleen Jones, Katherine Streckfus, Meredith Davies Hadaway, and Diane Landskroener were often roped into these projects, sometimes kicking and screaming but relenting and finally embracing the quest.

I recently looked at some of the more than 1800 emails between Bob and myself and wondered how I would ever write about him or describe him to a casual reader. His legacy at Washington College speaks for itself and the characters in his books are available to all, but what I will miss is his life-long contagious celebration of the arts, how they are meaningful to us and how void our lives would be without the telling of stories in word, music, or painting.

At the end of his short story, The Four-Wheel Drive Quartet, Bob writes, “We glow like algae split and rearranged by a great sailboat chased by the fall. We are components of music. We see ourselves in the maps we have made, and we draw lines with our movements. We are the paintings of flowers and windows. We are the electric soup. Nothing is mundane…”

The last line of both The Last Cattle Drive and its 2021 sequel For Not Finding You is “There is nothing more to write.” I understand.

For more about Bob Day and the founding of the Rose O’Neill Literary House, a ‘zine of recollections may be found here.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.