I was born on St. Patrick’s Day, so a lot of people wear green and get drunk on my birthday, but this celebration was a less boisterous, intimate gathering. A dozen friends had gathered in the living room of our white stucco four-square, and one of my sisters had driven quite a distance to attend. Locust logs flamed in the fireplace. Platters of smoked salmon, goat cheese and bruschetta had been arranged in the dining room and 100 white votive candles glowed softly on polished surfaces throughout the house. As a surprise from my family, nearly 50 photos depicting key moments in my life had been selectively scanned and those images rotated in no chronological sequence on the TV screen near the front windows.

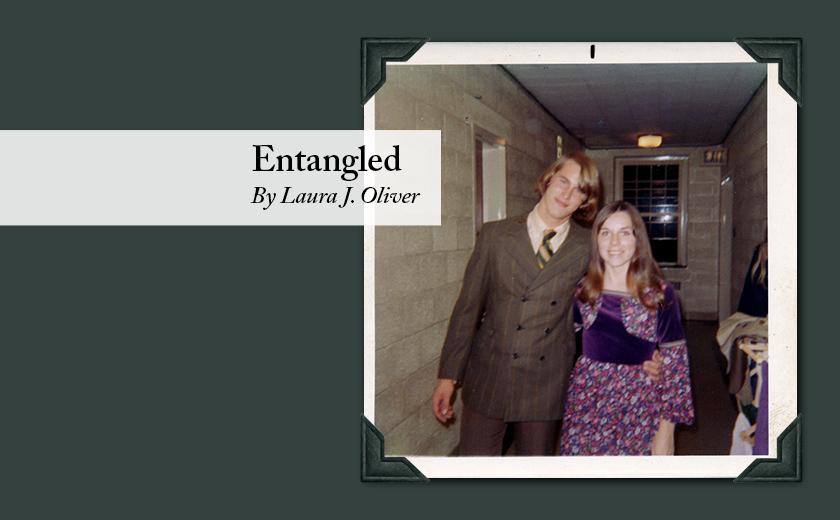

One moment, I cradled babies, newly born—the next, gripped diplomas, newly acquired. One moment I was a three-year-old in a stair-step pose with my older sisters, and in the next, I smiled from a cinderblock hallway in my freshman dorm with a classmate I’d just begun dating.

As I recall, Will and I were headed to a Kappa Alpha party that Saturday night where we would find the frat house smokey and dark, the floor sticky with beer, the bassline blasting from corner speakers with such intensity that every exchange of words required a tilt of the head as if to kiss or be kissed, a close leaning in, lips to ear. All evening this ritual elicited a smiling nod in response, then a quick pull back from each other to independently survey the room again. By the time we left, the K A’s and their dates were competing at beer pong, our hearing was temporarily impaired, and I had been excruciatingly not-kissed at least 30 times.

That night must have been a somewhat important occasion because Will had walked to Reid Hall to pick me up instead of just meeting me at the frat house. He wore a sports coat and tie. His blond hair hung long to his jawline. Fine-featured, a head taller than I, he looked like a guy who surfs in Malibu all summer and attends Princeton in the fall, which he was not. He also looked like the product of an exclusive Baltimore prep school, which he was.

My hair fell halfway down my back then. I wore a purple print dress with tiny flowers on the bodice, an empire waist and three quarter-length sleeves–-a little like a short version of something you’d wear to a Renaissance Festival. I wouldn’t buy it now, but I felt pretty in it that night. Smiling into the camera for all time, we were both 18 years old with the springy, untried optimism of foals.

Standing in my living room, I studied the face of the boy in the photo, his arm pulling me close by the waist in casual ownership, electric with innocence, wired with excitement for the evening ahead, and questioned whether what I recall of that long-ago night is even true. Neuroscientists claim that every time we remember an event, we distort it, and nothing is as unreliable as eyewitness testimony. I took a sip of my wine and wondered where he was at that moment and whether he planned to attend our next college reunion. The photo rotated abruptly, and Will disappeared.

Researchers who map memory have shared another revelation about the way the brain works: twenty percent of the population is plagued by an inexplicable sense of loss. That yearning is explained as a wistfulness for something those affected can’t identify; something they quite possibly never had, something that perhaps doesn’t exist. It’s just the way we’re wired.

It’s not at all a form of depression. I’m happy and laugh all the time. My life is good. But a sense of waiting has haunted me since the beginning of memory, as if something is arriving that will round out the emptiness—an emptiness I suspected only I harbor—until the revelations of this new research indicated I am not alone.

One morning about a week after encountering the image of Will and I, arms forever about each other in a dorm hallway, my college alumni magazine arrived in the mail, and I read that Will had died the previous spring. How could that be? What was I doing at the moment he left, I wondered? Waiting for a red light to change? Praising a fledging writer’s work? There was no mention of a wife or children and that grieved me. Lymphoma was the thief of his days and I imagined he suffered. That grieved me, too.

It had been decades since that college party, that relationship. After graduation, I never saw Will again, and most likely, never would have, yet holding the alumni news in my hand, my morning coffee steaming in the other, I felt an unreasonable sense of loss that the possibility of ever seeing him again no longer existed. Maybe that’s just another facet of the longing that shadows this perfectly good life. Where there is longing, there is hope. For what, I don’t know.

Sometimes I just want to go home. Only I am home.

I didn’t know the man Will became; I only knew the tender-hearted boy who walked me back to my dorm that night. I think it was a Maryland fall, a crisp night with leaves crunching beneath our feet as we crossed the campus arm in arm, but perhaps it was winter, and the stars were icy, the leaves long gone. Or perhaps it was March and we’d been at a St. Patrick’s Day party. Those facts are lost and don’t matter now.

What does matter is that love entangles us. What does matter is that if, like quantum particles, we remain in contact across all of spacetime with those whose hearts we’ve touched even once, there is no need for longing in the present or in the house of memory.

Because nothing can be lost. In the quantum world, this long-ago evening, and your life as well, have both happened and have yet to happen.

Which means somewhere there still exists a beautiful boy, a girl with an unlived life, the arrival of all you are waiting for, and a night starry with every possibility.

Laura J. Oliver is an award-winning developmental book editor and writing coach, who has taught writing at the University of Maryland and St. John’s College. She is the author of The Story Within (Penguin Random House). Co-creator of The Writing Intensive at St. John’s College, she is the recipient of a Maryland State Arts Council Individual Artist Award in Fiction, an Anne Arundel County Arts Council Literary Arts Award winner, a two-time Glimmer Train Short Fiction finalist, and her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her website can be found here.

Beautiful!

Such a talent for expressing the written word

Great work Laura. You are a master at sensory details and creating a vivid experience for your reader. Touching. A similar experience happened to me and I am reminded here of the loss I felt.