One afternoon in the 1970s, Chestertown real estate broker and property investor Vincent “Vince” Raimond made a discovery during the restoration of one of his houses on the corner of Kent St. and Cannon Street.

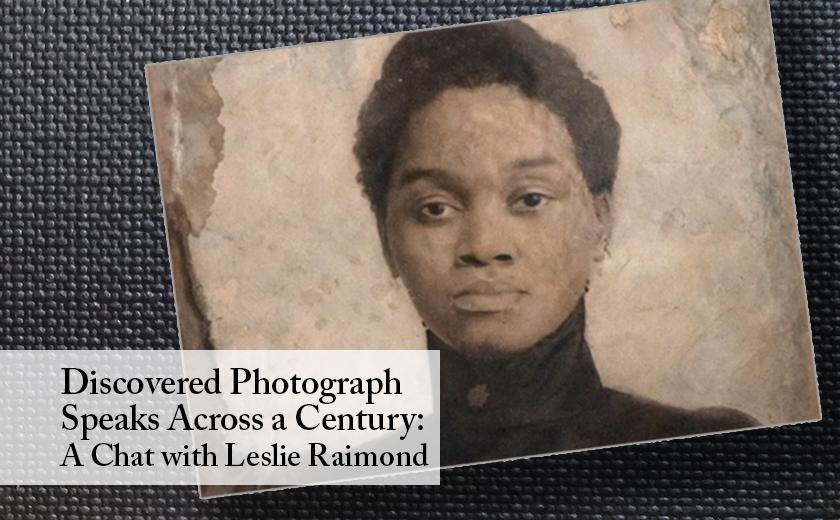

Removing an interior wall revealed a fireplace, and in it, a heavy, wadded-up lead sheet Raimond mistook for a cannonball. As he carefully unfolded it, a remarkable image of a Black woman in a high-collared black silk dress emerged. The image—perhaps an albumen print— was pasted to a five-pound lead sheet. It also looked as though part of the left side of her face had been re-touched, a common technique of scraping, drawing, or painting on the negative or directly on the print to remove blemishes or enhance angles in the face,

The mystery of the photograph is deepened by its provenance. The 111 Kent Street house once belonged to one of Chestertown’s famous Black forebears, James A. Jones. According to past research, parts of the structure probably date back to the 18th century. The house currently at the Kent Street address surely carries some of its previous colonial history.

The story of James A. Jones, a 19th-century Black Chestertown entrepreneur and political activist, is well-known. Among several political roles, as a founding member of Janes Church, and a successful business owner, Jones was one of several African Americans who confronted the town’s repressive voting laws by tactically using the same laws to acquire the vote.

Even after the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, Chestertown municipal voting laws required voters to own property. Jones, a fierce abolitionist, sold one square-foot sections of his property to freedmen, allowing them as landowners to vote.

Ironically, Jones bought several properties from Judge Ezekiel Chambers, a US senator, slave owner, and fugitive slave law advocate. It’s not a far reach to imagine that the same property was used to allow free Black men to vote.

Recent informal reviews and discussions about the photograph by fashion historians focus on the neckline and collar. “The neckline puts (her) between 1890-1910. Black silk was every woman’s “best dress” in those days. She is dressed like a lady, and she is beautiful,” one wrote.

Another added, “No shine, no ornament, no lace. This is the first stage of mourning for a close family member, spouse, parent, or child.”

But who is she?

Was she related to James Jones? Possibly. Jones died at 91 in 1894 within the time frame of the photograph. Is it possible that it’s Jones’ wife, Lucinda? There is no direct evidence to conclude that, but the fact that the photograph was found in the Jones house and that she wore a mourning dress fashionable for that period persuades us to continue to search.

The Spy recently interviewed Leslie Raimond to hear the original story of the photograph’s discovery. Her hope has always been to find a current family connection, even showcasing it at Charles Sumner Hall for several years without any hints of her identification.

It’s possible that someone you passed on High Street this morning may be this beautiful woman’s great-grandchild. Such is the complex warp and weave of Chestertown’s history.

This video is approximately seven minutes in length.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.